Don’t Underestimate the Role of the Individual in Civic Life

These days, it is regrettably easy to disparage the topic civics. To an enormous number of school boards throughout the country, civics is viewed as a subject to be avoided, lest there be a secret and dangerous lesson that would educate the student, thus producing a threat—possibly a well-educated mind. For the adult watching the evening news, there is the mantra of the politician: “Not to worry; everything is in good hands.” Civics lessons are unnecessary, since our system of government is doing just fine. “Trust us.”

I’m old enough to remember when lessons of our government, local and national, were passed along by school boards and teachers who saw the value in educating students, preparing them for life in the real world. Those lessons have stayed with me for my entire life. I am deeply grateful.

What happened? Perhaps history will help to answer that. I write historical fiction novels. With that background, I believe I can offer some relevant observations. People of a certain age, like me, were taught about the Founding Fathers. To many, it can be said that those men invented civics. Indeed, our entire system of government has been handed down to us by a relatively small group of men.

When we study these men, rarely do we weigh them as individuals—men with disagreements, with differing opinions, and different incentives.

Many of us were taught incorrectly that the “Fathers” were a single body: landowners, businessmen, and yes, slave owners. We are taught that 250 years ago, these men (only men) formed our first government, standing up as a single voice, in unity, to preserve this extraordinary New Idea. There are noteworthy paintings of these men gathered in a solemn setting, Independence Hall in Philadelphia, a single body, speaking out against King George, and planting the seeds of Revolution.

Note that “Founding Fathers” is almost always capitalized. When we study these men, rarely do we weigh them as individuals—men with disagreements, with differing opinions, and different incentives to stand tall against the king, or even to remain loyal to England at all. As my friend Ken Burns points out, the founding fathers (lower case) had absolutely no idea they were the Founding Fathers. None of them expected to have statues in their honor.

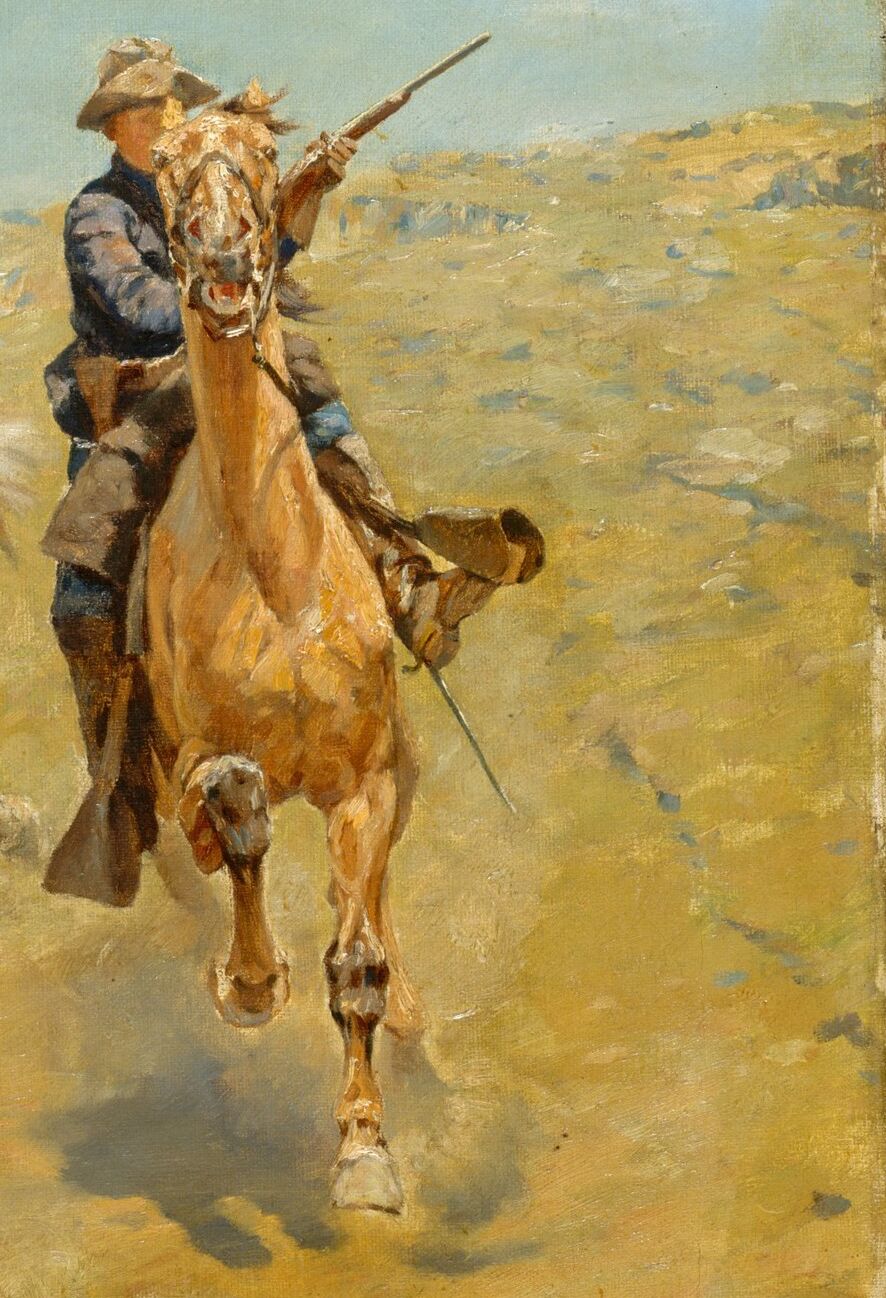

And they were not a united front. For example, the Carolinians angrily opposed the New Englanders on many of the issues they debated. The Declaration of Independence, though signed by representatives from each of the thirteen colonies, never had unanimous support. Indeed, these men should be congratulated for a great many things. To me, it should not be overlooked that every one of the men who signed the Declaration, who sat in Independence Hall, who debated the great issues of the day, the moment any one of them walked into Independence Hall, they put their necks in a noose. King George had declared them traitors. That is an astonishing act of courage. Had British soldiers suddenly showed up, there would be no Declaration of Independence, no Ben Franklin in Paris, no George Washington at the head of an army. Carry that analogy forward. There would be no Gettysburg Address, and there would be no such thing as American History, nor would there be any lessons on civics.

As with the Founding Fathers, it’s the people—and often, the individual—who creates history.

Another point, that I hope makes sense. I have written novels about the Revolution, the Civil War, World Wars I and II, and more recently, the Cuban Missile Crisis (October, 1962). Since I’m writing fiction, my primary goal is to find and tell a good story, while keeping the history as accurate as possible. I focus almost exclusively on the characters and their voices. As with the Founding Fathers, it’s the people—and often, the individual—who creates history. So many times throughout American history, our government is saved by extraordinary deeds, usually achieved by familiar names: Washington, Lincoln, Grant, Pershing, Eisenhower, to name a few (of many).

When it comes to civics, if we’re to learn the right lessons—especially from our own history—we must understand the power of the individual, the singular deed. What matters most? Honor? Honesty? Courage? Perhaps just simple competence. How hard can it be? If you can’t do the job, then step aside.

I regret to point out that not all deeds and actions included within the boundaries of civics are positive, beneficial to the people, or the nation. We must learn to recognize that as well and learn what’s wrong, or we’re destined to collapse back to the days of King George.

About the Author

Jeff Shaara is an acclaimed novelist and historian.