The Tenth Amendment

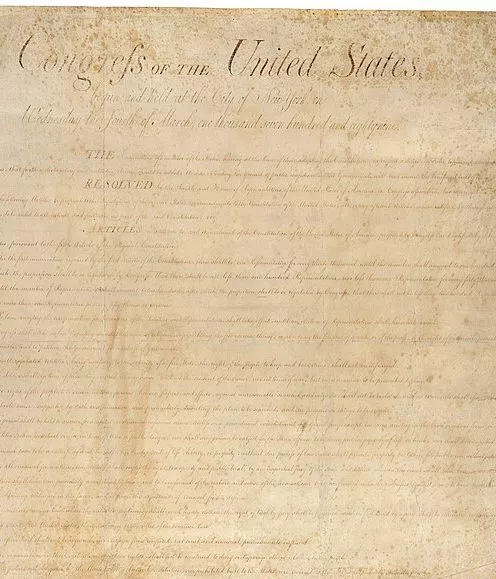

The Tenth Amendment was ratified on December 15, 1791 as a part of the Bill of Rights.

Retention of the people’s rights

When the U.S. Constitution was initially proposed and ratified, several members of Congress, especially within the antifederalist faction, took issue with its lack of a bill of rights.Antifederalists argued that a bill of rights would explicitly define the rights of the people, in effect preventing them from being violated. Several state constitutions contained a bill of rights – if the federal government took precedent to state government, it followed that the federal constitution should have one as well. In contrast, federalists such as Alexander Hamilton, did not believe a bill of rights was necessary. Since the government was limited to its delegated powers, it seemed unnecessary to define the rights of the people. In fact, some federalists thought a bill of rights was a dangerous concept – rights omitted may be considered unretained.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

In the end, the antifederalist concerns were heeded as several states ratified the Constitution on the condition that a bill of rights would be added. After the Constitution’s ratification in 1788, James Madison drafted the Bill of Rights, drawing inspiration from the Virginia Declaration of Rights and amendments proposed by the states during ratification. He initially recorded 19 amendments; the House and Senate pared these down to 12 before they were sent to the states for ratification. The first 2 amendments, which pertained to apportionment in the House and pay for Congress, were rejected by the states, leaving the first 10 amendments as we know them today.

Along with the Ninth Amendment, the Tenth Amendment addressed the concern of many federalists: that rights omitted would be rights unretained. The Tenth Amendment stressed that powers not delegated to the United States, nor prohibited to the individual states, would, by default, always be retained by the states/people – NOT the federal government.

Resources on the Tenth Amendment

A collection of resources recognizing this important piece of American law.

Passage of the Bill of Rights

Only a month after the Constitution was printed and distributed, the first ratifying convention took place in Pennsylvania. The ratification process went relatively smoothly for a couple of months after that, with five state conventions approving ratification with little difficulty.

In January of 1788, however, the ratifying convention in Massachusetts devolved into a bitter and even violent deadlock, largely over the question of a bill of rights. Only by promising to introduce a Bill of Rights as amendments were the Federalist supporters of the Constitution able to break the deadlock and secure ratification in Massachusetts. Without this strategy, which was subsequently adopted in other states with Federalist minorities, the Constitution could not have been ratified.

Despite the reservations of many of the Federalists, who had a commanding majority in the first Congress, James Madison recognized the necessity of keeping their promise and adding a Bill of Rights quickly in order to secure the legitimacy of the new government. He submitted a proposal for seventeen amendments based on the Virginia Declaration of rights early in 1789.

This proposal went through four stages of rigorous debate and revision in the House and the Senate before being approved by Congress in September of 1789. Of the twelve articles in the approved amendments, ten were ratified as by the states over the course of the next two years, becoming what is now known as our Bill of Rights. The first of these ten included the provision that “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.”

Read more about the Bill of Rights

at ContextUSThe Bill of Rights

December 15, 2021 will mark the 230th anniversary of the ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791. When the U.S. Constitution was initially proposed and ratified, several members of Congress, especially within the antifederalist faction, took issue with its lack of a bill of rights. In recognition of the Bill of Rights and its place in constitutional ratification, JMC presents a collection of firsthand commentary, fellows’ articles and other online resources on the Bill of Rights.

States’ rights and the Tenth Amendment

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

- Sotirios A. Barber, “The Fallacies of States Rights”

- Sotirios A. Barber, “National League of Cities v. Usery: New Meaning for the Tenth Amendment?”

- Sean Beienburg, “Prohibition, the Constitution, and States’ Rights”

- Keith Dougherty, “An Empirical Test of Federalist and Anti-Federalist Theories of State Contributions, 1775-1783″

- Vincent Phillip Muñoz, “State Police Powers and the Founders’ Constitutionalism”

- Benjamin E. Park, “Jeff Sessions is a Hypocrite on States’ Rights. But So is Everyone Else”

- Robinson Woodward-Burns, “Hidden Laws: How State Constitutions Stabilize American Politics”

- Emily Zackin, “Looking for Rights in All the Wrong Places: Why State Constitutions Contain America’s Positive Rights”

Commentary and articles from JMC Scholars

The Bill of Rights

Jeremy Bailey, “Was James Madison ever for the Bill of Rights?“ (Perspectives on Political Science 41.2, 2012)

Warren M. Billings, “‘THAT ALL MEN ARE BORN EQUALLY FREE AND INDEPENDENT’ Virginians and the Origins of the Bill of Rights.” (The Bill of Rights and the States, 1607–1791, 1991)

Michael Douma, “How the First Ten Amendments became the Bill of Rights.” (Georgetown Journal of Law and Public Policy 15.2, 2017)

Justin Dyer, American Constitutional Law, Vol. 2: Liberty, Community, and the Bill of Rights. (West Academic Publishing, 2018)

Arthur Milikh, “Rethinking the Bill of Rights.” (National Review, December 15, 2016)

Thomas Pangle, “The Philosophical Roots of the Bill of Rights: The Federalists’ and Anti-Federalists’ Conceptions of Rights.” (The Political Science Teacher 3.2, Spring 1990)

Thomas West, “The Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.” (The Declaration of Independence: Origins and Impact, CQ Press, 2002)