An interview with Alex E. Hindman

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC scholar Alex E. Hindman to discuss separation of powers, the constitutional presidency, and America’s civic religion. Dr. Hindman is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the College of the Holy Cross.

ED: What inspired you to become a political scientist?

AH: I was always civically minded growing up. My grandfathers were World War II veterans, which influenced my childhood. We were taught to love America, but it wasn’t until my time at Saint Vincent College that I began to appreciate the American Founding for the ideas it left us, more than its historical moment. The coherent set of answers it provides to the human condition, focusing on equality and natural rights, captured me early. Then the September 11th Attacks, while I was an undergraduate, solidified my commitment to these ideas and drove me toward this work in the hope that I could teach others about it. I had critically important teachers at key moments to spur me forward.

ED: What is your specialty area, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

AH: I focus on American institutions and their interactions under the separation of powers. My work examines how the law forms, shapes, and channels the perspectives and range of actions available to constitutional officeholders. How do constitutional actors seize the gaps in the law to act, and in what ways do the laws shape their character? I’ve always been fascinated by James Madison’s argument in Federalist No. 51 about the “interests of the man being connected to the constitutional rights of the place.” The binding of personal ambition with institutional loyalty in the constitutional system and then turning those ambitions against each other was one of the most innovative ideas in Western democratic theory.ie vehicula.

I was hooked once I read the Federalist closely as a work of political philosophy and saw the separation of powers as a defining, constituting feature of American political life.

Ford and the Constitutional Presidency

ED: Tell us a little bit about your most recent work on Gerald Ford.

AH: My book, Gerald Ford and the Separation of Powers, argues that President Gerald Ford took office facing tremendous political difficulties after Vietnam, Watergate, and his subsequent pardon of Richard Nixon. He came to office as an unelected president and would face veto-proof partisan opposition in both chambers of Congress after the 1974 midterms. Under the “modern presidency” theory, his presidency should have been a failure by every measure. Yet, I argue, Ford was able to use the constitutional presidency as it was designed to have a modestly successful term. In the archives, I found that the late Robert Goldwin, of Kenyon College and later AEI, coached Ford through Alexander Hamilton’s case for the veto. Ford repackaged Hamilton’s ideas in his public statements. In the end, I show that politically unpopular presidents are still fully constitutional presidents, as Ford discovered, and he could use the Constitution as it was designed to preserve the presidency.

ED: What are some aspects of “separation of powers” that many Americans might not consider when thinking about or discussing US politics?

AH: The separation of powers is to American politics what the wood framing is to your house. You don’t always see the floor joists or the studs in the wall, but they’re there, and you’d live in a much different house if they were not. The separation of powers is much like that substratum of American life. Rather than raw politics driven by power only, the separation of powers constrains politicians from transgressing into the powers of the other branches or the rights of citizens. Today, many Americans would be well served to rediscover the value of the Madisonian Constitution and its operation. The Jack Miller Center’s work is critical to restoring institutional loyalty in partisan times. However, the short fundamental truth remains that the American separation of powers makes “ambition to counteract ambition” on a principle drawn from antiquity, that none of us has a perfect picture of justice. We’d all be well served to check our hubris in our polarized society. If we embrace our Constitution, the separation of powers could help us see each other anew.

Reaffirming Principles

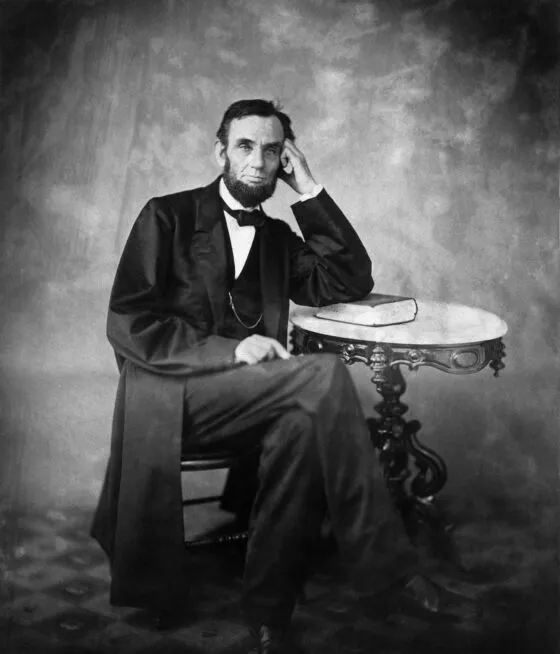

ED: Which figure from your research has taught you the most about the value of America’s founding principles and history?

AH: Abraham Lincoln taught me the value of the Declaration of Independence, which formed Americans’ character in equality and continues to hold us accountable when we’ve failed to live up to our ideals. He demonstrated that it is possible to appreciate the truths we uphold, even if we do not always meet them. However, Lincoln redeems the nobility of the framers’ cause in reaffirming these principles, even as they fell short of their own expectations. In this way, he vindicates their ideas despite their shortcomings, particularly regarding slavery. Moreover, his words serve as a lesson to anyone who feels marginalized in our society today.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about the American political tradition?

AH: I think that the American framers were inherently practical people as opposed to other founders of other countries. Richard Beeman’s excellent book, Plain Honest Men, makes this argument. The framers disagreed, fought, and hashed out significant differences to form a country rooted in human nature, both its virtues and vices. They took Americans as they knew them to be, selfish at times, and great in others. Moreover, they did not try to make men something they were not, nor deny them the chance to rise to greatness. Ideology took a back seat to practical political considerations, which is why the bundle of pragmatic compromises at the core of the American political tradition frustrates scholars who try to fit the Early American Republic into little boxes.

The American political tradition remains an ongoing invitation to deliberate and engage with each other as fellow citizens. If the Constitution is embraced as Lincoln says as America’s “civic religion,” we might be able to hold our increasingly pluralistic and polarized society together.

ED: Excellent, thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).