An interview with Andrew Porwancher

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Fellow Dr. Andrew Porwancher to discuss his new book, American Maccabee: Theodore Roosevelt and the Jews. Dr. Porwancher is the Director of Graduate Studies and Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership.

ED: For those of us who haven’t studied Theodore Roosevelt, what are a few notable events from his life that we need to know before reading your book American Maccabee: Theodore Roosevelt & the Jews?

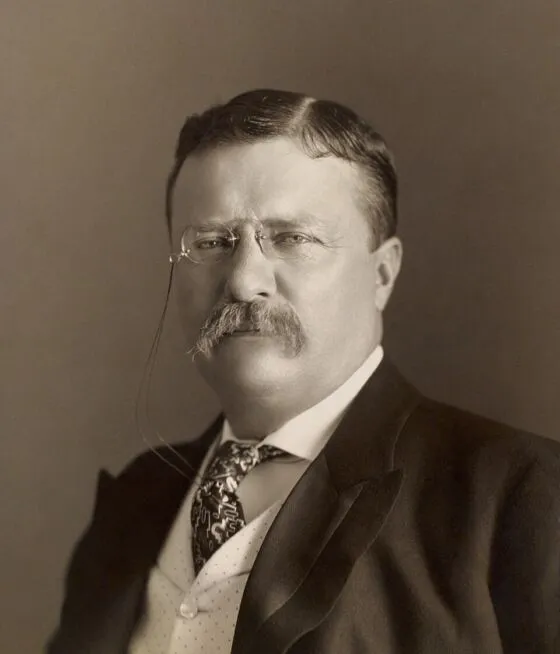

AP: Roosevelt had a meteoric rise in American politics with few parallels in our nation’s history. He became the police commissioner of New York City at just 36. Then President William McKinley appointed him Assistant Secretary of the Navy at 38. Roosevelt was leading the Rough Riders into battle in the Cuban hills at 39. He returned home a national hero and was elected governor of New York at 40. The Republican Party nominated him to join the national ticket as a vice-presidential candidate at 41. McKinley’s assassination elevated Roosevelt to the White House at the record age of 42. This extraordinary ascent took place over six short years. What I aim to show in my book was that the Jewish people played an important role in each successive step.

An ancient title

ED: Tell us how you chose the title of your book, and please explain some of the ways that Roosevelt tried to combat antisemitism.

AP: I chose the title American Maccabee because Roosevelt venerated the Maccabees, the ancient Jewish warriors who rebelled against Greek rule. He looked for “the Maccabee type” while recruiting Jews for the NYPD—that is, Jews whose bravery and hardihood aligned with Roosevelt’s deeply held notions of courage. When he once wrote, “I wish I had a little Jew in me,” he undoubtedly had in mind this ideal of the American Maccabee.

AP: His efforts to combat antisemitism assumed many forms. In Roosevelt’s first year with the NYPD, a notorious antisemite planned a lecture in New York, prompting Roosevelt to cleverly assign him a police detail that consisted solely of Jewish officers. Roosevelt also made efforts at every stage in his career to appoint Jews to positions of import. And most notably, as president, he spoke out against the violence perpetrated against Russia’s Jews when no other head of state dared to challenge the czar in this way.

ED: Studying Roosevelt so deeply must have led to an epiphany or two about his life and times. What surprising “eureka!” moment did you experience while writing about Roosevelt?

AP: My favorite “eureka!” moment came toward the end of my research. It seemed fitting to end the book where biographies often do—with the subject’s passing. But I wasn’t sure how to make that moment relevant to my Jewish theme until I came across a newspaper article about the night before his funeral. It turned out that the lone soul permitted to keep watch over Roosevelt’s body was a Jewish refugee from Russia. His name was Otto Raphael, and he had come to Roosevelt’s attention decades earlier when Roosevelt led the NYPD. Back then, Raphael had just become a local hero in Manhattan’s Jewish enclave for rescuing people from a burning building. Roosevelt recruited him to the police force, and the two soon became sparring partners in the boxing ring. Theirs was a friendship that lasted until the very end, as testified by Raphael’s vigil on that final evening before Roosevelt’s burial.

ED: What sort of personality quirks or idiosyncrasies did you uncover while researching Roosevelt? Did he have any favorite sayings or habits? Which primary sources helped you uncover these quirks?

As a historian, I am always scouring the archives in search of hidden gems in personal correspondence. Roosevelt was an especially prolific letter-writer, so the archival fodder is abundant for his biographers. And one of the quirks I noticed in his letters was a tendency to use exclamation points—sometimes more than one at a time. When Russia tried to extradite a freedom fighter who had sought political asylum in America, Roosevelt capped off an exasperated letter to his secretary of state with a double-barreled “Oh lord!!”

Roosevelt’s memorable sayings

AP: Roosevelt certainly had his share of sayings, perhaps most notably “Bully for you!” when he wanted to signal encouragement. He also loved the term “square deal.” Roosevelt believed that in a fair America, everyone should get a shot to succeed but no one should be handed any special favors. When a Jewish undergrad at Harvard published a piece in Menorah magazine lauding Roosevelt for treating Jews on an equality with other citizens, Roosevelt happily relayed to a Jewish advisor that this college student had “grasped exactly what my attitude is”—to wit, “each is to have a square deal, no more and no less.”

ED: What sets your book apart from other works on Teddy Roosevelt?

AP: Writing about Roosevelt was a pleasure in no small part because I had so many excellent works of scholarship to draw from. But no other book before mine had focused on Roosevelt’s relationship with the Jewish community. The absence of such a study is striking given the depth and texture of that relationship—Jewish people and Jewish causes surface at every turn of his story. My ambition was not to write a narrow study, but rather, to use the Jewish angle to engage larger questions about American civic life.

ED: Continuing a trend that started in the 1960s, most historians today practice social history, i.e., studying the history of ordinary people rather than leaders. What are some of the benefits and deficiencies of studying ordinary people versus studies like yours, which focus on presidential history? Do you believe that presidential history will make a comeback?

AP: The grassroots approach to history can be both instructive and limiting. It is instructive when it affords us a window into experiences in American society that were left largely neglected prior to the 1960s. It is limiting when it fails to account for the profound role of political leadership in shaping the American past.

Ultimately, my hope is that American Maccabee can combine the best of both traditions. My book takes readers into the inner sanctums of presidential power and the sweatshops of Jewish slums. Indeed, the story of Roosevelt and the Jews demonstrates the necessity of an integrated approach to history that attends to the White House and the tenement house alike.

Presidential history could and should make a comeback in academia. Many leading state universities around the country have newly established civics programs—modeled after my own at Arizona State University—that would surely be amenable to hiring presidential historians. And hopefully that kind of market demand will encourage graduate students to embark on presidential studies with fresh optimism.

ED: What has studying and writing on Roosevelt taught you about the American Political Tradition?

My experience writing this book helped me appreciate how Roosevelt embodies the American Political Tradition with all its constructive contradictions.

AP: He was a rugged individualist and a believer in communal action, a military hero and a Peace Prize laureate, an idealistic champion of American intervention abroad and a cautious realist who showed restraint on the world stage. Much of American history can be understood as a spirited debate between competing values. The result is a political culture that—fractious though it may be—ensures new ideas get properly stress-tested. Theodore Roosevelt personified the productive paradoxes of our boisterous democracy as much as any president.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Dr. Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).