An interview with Barry Strauss

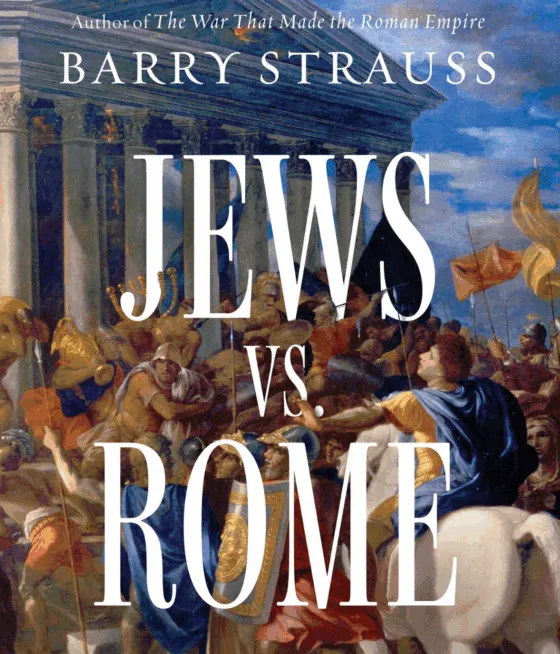

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC academic council member Barry Strauss to discuss his new book, Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World’s Mightiest Empire. Dr. Strauss is the Corliss Page Dean Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University as well as the Bryce and Edith M. Bowmar Professor in Humanistic Studies Emeritus at Cornell University, where he is the former Chair of the Department of History as well as Professor of History and Classics.

ED: Having written on many fascinating and important aspects of the ancient world, from Spartacus to the Caesars, what inspired you to write Jews vs. Rome?

BS: I had three reasons for writing Jews vs. Rome. I was intrigued, first, by the good relations between ancient Iran, Parthia, and ancient Israel, Judea, which are such a contrast to the current situation, in which the Islamic Republic of Iran has committed itself to the destruction of the Jewish state. I wanted to learn more about Parthia and the Jews. Second, I wanted to bring to life the story of certain people, good and bad, who had been overlooked by most historians. It was an era that included some of the most famous and important people in history, from Jesus and Augustus to Cleopatra and Hadrian. Yet some of the lesser-known names are equally fascinating. I knew that, as a historian, I could bring their lives to light.

Third, and above all, my hypothesis was that by studying the revolts, and the rabbis’ response to them, I might learn something about the “secret sauce” that explains Jewish endurance over the millennia of exile and, frequently, of persecution.

Caught between empires

ED: Caught between empires, what made the geopolitical realities of Judea so unique?

BS: Judea, ancient Israel, was a small state caught between two empires, a western empire, Rome, and an eastern empire, Parthia—that is, ancient Iran. Any state in that position would naturally try to balance between the two titans on either side of it. To complicate matters, each empire had invaded and conquered Judea. Rome was more successful, and its rule was more durable.

Parthia controlled Judea for only three years, but it retained many supporters there, and it could capitalize on the fond memories of an earlier Iranian regime that governed Judea for two centuries, the Achaemenid Persians. Another complication was the Jewish Diaspora. It stretched westward in Roman realms from Syria and Egypt to Libya and Italy. It stretched eastward in the Parthian empire from northern Mesopotamia to Babylonia to Iran. The Diaspora populations gave Judea additional support while also making it suspect in one or the other of the two empires.

ED: You write that Roman-Jewish relations “worked until they didn’t.” What led to the unraveling of this relationship—and to what extent were Jews themselves united in their views about the Romans?

BS: It took statesmanship to keep Jewish-Roman relations in Judea on an even keel. Rome considered Judea to be a client kingdom first, and then, a Roman province. Jews considered Judea to be the Holy Land, whose only king was God. Rome considered Caesarea-by-the-Sea to be the provincial capital; Jews gave that distinction to Jerusalem, and above all, to the House of God that the Temple represented. If pushed, a compromise between the two positions was not possible, but some men knew not to push it.

Herod the Great was a bloody tyrant, but he shrewdly managed relations with Rome. He built up both the Jewish character of Judea, most notably in his monumental rebuilding of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, and the pagan character, for example, in three temples to the emperor Augustus. Augustus, for his part, funded daily sacrifices on behalf of the emperor, carried out by the Jewish priesthood in the Temple. Much of the Jewish elite approved of such compromises but a part of the population looked down on them as a desecration of the Holy Land. Herod’s dynasty did not last, and Augustus gave way to irresponsible and bloodthirsty emperors such as Gaius (Caligula) and Nero. Their behavior convinced many that the Romans were threats to Jewish survival. The statesmen were gone. The stage was set for conflict over Judea.

ED: Many readers know about the destruction of the Second Temple, but may not be familiar with the other revolts, like the Diaspora Revolts or the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Were there common threads between all three revolts—and what was truly at stake for the Jews?

BS: The Great Revolt (66-70 CE), also known as the Jewish War, is known to many readers, especially its most famous incident, Masada (74 CE), where more than 900 Jews chose death before enslavement. But there were two other large-scale Jewish revolts in the High Roman Empire and several small ones. These were the Diaspora Revolt (116-117 CE) and the Bar Kokhba Revolt (132-136 CE). Despite many differences among them, the three rebellions are linked by a common thread: the desire of the Jews to be a free people in their own land. All three revolts pitted Jewish soldiers against the mighty Roman legions. It was an unequal contest. The Romans destroyed Jerusalem, the Holy City, and the Temple in the first revolt, so in the second and third revolts, rebuilding both city and temple were of the highest priority.

ED: Berenice of Cilicia came from the Herodian dynasty—a Jewish royal family that ruled parts of the eastern Roman Empire. Because of her royal position, she may have had more freedom than most women of her time. In a society where men usually held power, how was she able to play an important role in politics?

BS: Berenice, Queen of Chalcis, played a surprisingly important role in Roman-Jewish relations for fifteen years between 66 and 79 CE. This is surprising both because she was a woman and because Chalcis, in today’s Lebanon, was small and insignificant. Yet this queen without much of a throne was a major player. The reasons: she was the granddaughter of King Herod the Great of Judea. She was also the sister of King Agrippa II who ruled what is now northern Israel and parts of Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. Agrippa II was a bachelor and Berenice served as a kind of unofficial First Lady. No less important, she was savvy, charming, ambitious, and courageous. She was a pious Jew in some ways, but she was loyal to Rome and dead set against the Great Revolt, which she opposed openly and at a risk to her life. Most important for her, she became the mistress of Titus, son of the Roman commander Vespasian in Judea. Later, Titus became conqueror of Jerusalem and, finally, emperor in his own right.

Besieger and besieged

ED: Both the Jews and the Romans understood the symbolic nature of Masada. You write how the site was a “station on an ancient version of an Underground Railroad.” What symbols did Masada evoke, and what were some of the challenges faced by both the leaders of the besiegers and the besieged?

BS: Masada was the last bastion of Jewish freedom of Rome in the Land of Israel. For the rebels, it represented hope; for the Romans, defiance. This is why one side made the ultimate sacrifice rather than surrender it, and why the other could accept nothing less than snuffing out disobedience to the empire. To be sure, like most things concerned with the Great Revolt, Masada was not an unambiguous symbol. At one point, to gain supplies, the rebels attacked a Jewish settlement nearby and massacred the inhabitants, their fellow Jews. To conquer Masada, Rome had to put together a large force and supply it with food and water in the desert. They had to surround the fortification, build camps, and construct a ramp to reach the top. The rebels were well-supplied with food and water, but they were outnumbered more than 10:1, and so they had to find a way to win if somehow, anyhow, that was possible.

ED: Looking at the ancient world—particularly the era of Jewish revolts against Rome—are there aspects of life or belief from that time that you think we’ve lost, to our detriment?

BS: Few people would want to experience the suffering, deprivation, enslavement, betrayal, senseless hatred, torture, or death that were the lot of many people during the Jewish revolts against Rome. There were, nonetheless, qualities present then that we would do well to emulate today. Resilience, determination, faith, endurance, self-sacrifice, and patriotism were hallmarks of the rebels. The Romans were brutal and they crushed local independence. Still, one might admire their dedication to order as well as their military discipline.

The rebels showed an iron-willed commitment to freedom from foreign rule—not on behalf of some narrow chauvinism but, rather, in service of what they considered the holiest and noblest of ideals. To ask if we have enough of those qualities today is to answer.

ED: Ultimately your book serves as inspiring example of resilience. Do you have a favorite Jewish figure from your work who you believe embodies the Jewish struggle for survival?

BS: The violent resistance of the rebels and the spiritual resistance of the rabbis who followed them were two sides of the same coin: Jewish resilience. They disagreed about the practicality of taking arms up against Rome but not of the need to oppose what it stood for. Rome meant surrender of the holiness of the Land of Israel, surrender of faithfulness to the one and only God, and surrender of Jewish exceptionalism. Perhaps the person who exemplifies this spirit best is Rabbi Akiva. He refused to give up hope after the destruction of the Second Temple. He is said to have supported the rebellion of Bar Kokhba. He died a martyr’s death around 135 CE at the hands of the Romans. His students preserved his teachings, and they were foundational to the Mishnah, the basic text of rabbinic Judaism and hence of the survival of Judaism as a religion.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Dr. Elliott Drago is the JMC’s Manager of Network Engagement and Resident Historian. His research focuses on the politics of slavery in the United States and his book is entitled Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2022).