An interview with C.C. Borzilleri

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Fellow Dr. C.C. Borzilleri to discuss her work on women, gender, and print culture in early American history. Dr. Borzilleri is a project coordinator at the Bill of Rights Institute.

ED: Congratulations on your recent dissertation defense! What inspired you to become a historian in the first place?

CCB: Thank you! It has been a long time coming, and luckily the process of blood, sweat, and tears has been (mostly) figurative. My early life and childhood were heavily influenced by my hometown, Litchfield, Connecticut, being steeped in early American history and its legacy. At the turn of the nineteenth century, Litchfield was the site of the Tapping Reeve’s Law School, the first law school in the United States, as well as Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, a leading school for young women to be educated in some of the same subjects and disciplines as their male peers, including geography, Latin, and arithmetic, alongside more traditionally feminine skills like embroidery, playing music, and dancing.

I grew up surrounded by the stories of early Americans’ lives as though they were my contemporary neighbors, which has helped me to bridge the gap between past and present in my own understanding of history throughout my life. The direct lines connecting the past with the present have always been an inspiration for me, and I love that now in my career I get to work with the ideas and concepts of history in the context of modern situations.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

CCB: The title of my dissertation is “At Her Print Shop: Women and the Print Trade in Early America.” My work has a few big themes: the history of women and gender, the early American period during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the way that print culture has both influenced and been influenced by society.

Academic outcomes

CCB: During my undergraduate years at Georgetown, I worked on an honors thesis studying the outcomes of women who attended the Litchfield Female Academy between 1792 and 1833. Many of those women pursued careers that were essentially professional even when their world did not readily invite women into official positions of power and influence. Several served as magazine editors in the mid-nineteenth century, and that piqued my curiosity to search for historical antecedents. Women printers of newspapers during the American Revolutionary Era and the period of the Early American Republic quickly fascinated me.

CCB: I have come to describe women printers’ relationship to their gender as both limiting and liberating, which is perhaps a cliched historian way of saying “it’s complicated!”, but I think this framework has some very important features that are transferable across a wide range of historical periods and subjects. Very few events or decisions are clearly black and white.

For the women whom I was studying, I found that the primary identity that they presented to the world was “printer” rather than “woman.” Although there were several dozen of them at any given time, and many were well-known throughout their regions and even across the early United States, there was not a sense of camaraderie or group-consciousness that bound them together as “women printers.” This is one of the most surprising aspects of my research for modern audiences of historians and non-historians alike who typically ask me what other sort of proto-feminist activities these professional women got up to with their positions of power. These women printers certainly exercised influence in their societies by nature of their careers, and they provided an exemplar to their communities of women defining their own roles in society, but it is ahistorical to assume that their motivations for building careers in the public eye were based upon their gender politics or an animosity towards the patriarchy. Meanwhile, their views on political events would often shine forth as clearly as they did for their male contemporaries, and these women were often taken just as seriously in their political convictions as their male peers. You see what I mean about “it’s complicated”?!

ED: Tell us about your favorite primary source that you uncovered during your research.

I have come to describe women printers’ relationship to their gender as both limiting and liberating, which is perhaps a cliched historian way of saying “it’s complicated!”, but I think this framework has some very important features that are transferable across a wide range of historical periods and subjects. Very few events or decisions are clearly black and white.

CCB: For the women whom I was studying, I found that the primary identity that they presented to the world was “printer” rather than “woman.” Although there were several dozen of them at any given time, and many were well-known throughout their regions and even across the early United States, there was not a sense of camaraderie or group-consciousness that bound them together as “women printers.” This is one of the most surprising aspects of my research for modern audiences of historians and non-historians alike who typically ask me what other sort of proto-feminist activities these professional women got up to with their positions of power. These women printers certainly exercised influence in their societies by nature of their careers, and they provided an exemplar to their communities of women defining their own roles in society, but it is ahistorical to assume that their motivations for building careers in the public eye were based upon their gender politics or an animosity towards the patriarchy. Meanwhile, their views on political events would often shine forth as clearly as they did for their male contemporaries, and these women were often taken just as seriously in their political convictions as their male peers. You see what I mean about “it’s complicated”?!

ED: Tell us about your favorite primary source that you uncovered during your research.

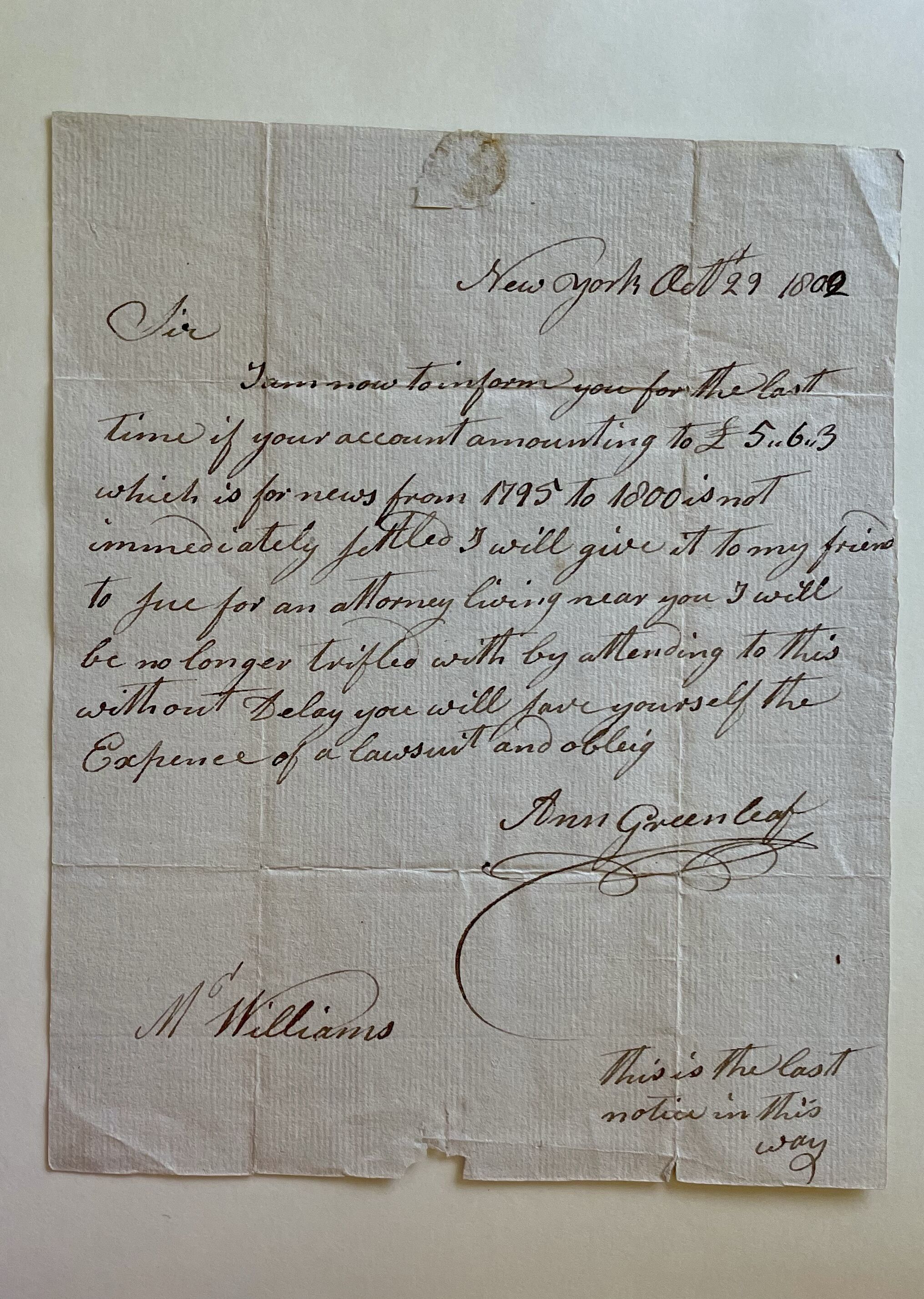

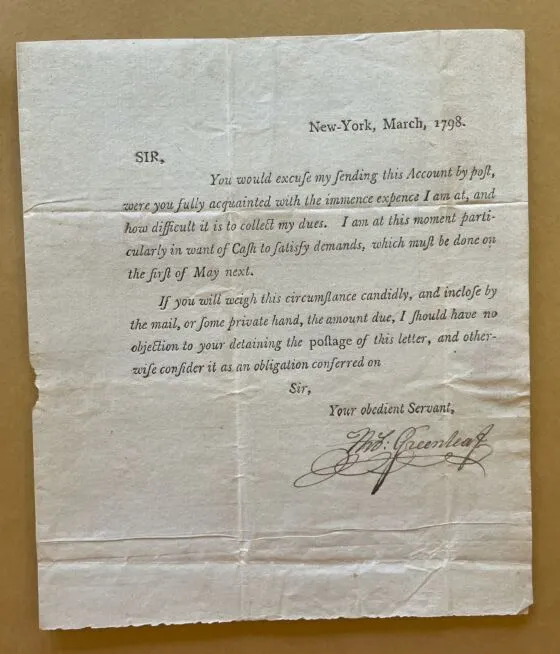

CCB: One of the absolute best sources I found was a letter from Ann Greenleaf to Sam Williams in Vermont demanding payment of over three years of subscription fees for the newspaper he had been receiving. Backing up a little bit, Ann Greenleaf was the publisher of a regular newspaper in New York City following the death of her husband, its previous publisher, Thomas Greenleaf in 1798. As she took over the paper, she proved herself to be just as technically skilled and as politically opinionated as her late husband. The business she took over, however, had a slight cash flow problem; like many early American newspapers, subscription payments could be delinquent for a period of years before the subscriber faced consequences. While doing research at the Vermont Historical Society I discovered a trove of overdue payment notices kept by eighteenth century Vermonter Samuel Williams, including some from both Ann and Thomas Greenleaf.

Williams had received a letter from Greenleaf’s late husband, Thomas, which gave me the chance to see the difference in tone and approach between husband and wife in their management of the print business. While Thomas had leaned into the cultural norms of apologizing for bringing up something as vulgar as money and seemed to waffle a bit about the purpose of sending such a notice, Ann was not interested in beating around the bush nor offering any additional leeway for Williams. She very clearly laid out the amount needed and her willingness to pursue legal action against Williams if he did not pay up as soon as possible.

Norms and niceties

I have no idea whether Williams ever sent the money he owed to Greenleaf. But the record of that demand for payment remained in his financial papers that survived to his death and remains preserved in perpetuity at the Vermont Historical Society, which lends a lot of legitimacy to just how seriously he took that missive from Ann Greenleaf. Greenleaf’s disregard for social norms and niceties in her business correspondence really struck me as significant as I tried to piece her life together. She was, at this point, the mother to several young children and essentially a mother-figure to the apprentices and employees in her print shop, but she did not draw upon maternal or feminine ways of presenting herself as she carried out her business.

ED: What advice would you give young scholars planning to major in history?

CCB: I paired my history major in undergrad with a second major in government and a minor in psychology. I loved getting the interplay across each of these fields and making connections in my classes and assignments to the other things I was studying at the time. Particularly through psychology, I felt like I was becoming a better historian by diving into how the human brain makes sense of its surroundings, connects with other people, and assesses different situations and needs.

This foundation really informs how I look at historical sources. One of my favorite items I have ever seen in an eighteenth-century newspaper – and I’m kicking myself for not making note of the specific issue – was a front-page article announcing the specific distance in miles between New York City and Albany. This would help people making journeys from one city to the other know how long it might take and where and when they might have to rest themselves or their horses. I loved seeing this notice and being forced to think about the world-building and concepts of place and space that were present or absent in the eighteenth century compared to today.

I love exploring how people in the past conceptualized the world around themselves, and it is often an exercise that makes me more aware of my own place in the present by challenging the things that are easy to take for granted. Like knowing what any given place looks like from above, having instant communication with friends and family members across the world, and being able to access answers to almost any question in just the time it takes to type out a quick search.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

CCB: So many events in the course of history are the result of people facing problems and solving them with the tools they have at hand. In the cases of my women printers, the problem of sustaining their family’s livelihood could be solved with the use of the tools: an inherited printing press and set of skills to make it produce valuable outputs.

In the case of the founding of the United States, the problem was even more broadly existential: how to build a new country that would both protect the security and respect the liberty of its citizens? The tools of the founders were slightly more ephemeral than those of the printers, but this made them even more important. Reliance on ideas of justice, liberty, and equality as the underpinnings of a representative government has proven to be of enduring value.

In a very specific sense, my scholarship about printers has also made me consider the way that we know history. My subjects, women printers and publishers of newspapers, created an extensive paper trail throughout their lives which distinguishes them significantly from many of their contemporary early American women. To have a regularly printed document that lists a publisher’s name and location at weekly intervals? A historian’s dream! And that trail has been useful to scholars even when they have not realized that they were relying on records produced by women.

One of my favorite discoveries while doing dissertation research was at the Clements Library at the University of Michigan, where I found that nineteenth century author and historian Peter Force had been collecting news items about the American Revolution to write his definitive record of the conflict, and he had been taking notes on paper produced by mill that one of my subjects had owned. So even though Force did not mention Revolutionary era printer Hannah Watson by name, the content from her presses and the products from her paper mill were foundational to his work.

Throughout the 1770s, Hannah Watson had faced a series of obstacles in her career – being widowed, losing her mill to a fire set by Loyalists, and facing the rag shortage that threatened every printer in the colonies during the Revolution – but like her contemporaries in Philadelphia who were trying to use what they had to establish a new and united nation, she was able to overcome these challenges in Hartford, Connecticut, to build and maintain the foundation of what would become an intellectual and literary hub of activity for several decades to follow.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

CCB: The “big” events of history were taking place at the same time as the small events of daily life. George Washington ate breakfast, and Abigail Adams got dressed in the morning. Sometimes both surely suffered from headaches and realized that they hadn’t had any water to drink yet that day.

The characters of history were occupying human bodies with regular needs, wants, and patterns that we are exceptionally and intimately familiar with. Being a historian is made somewhat easier when you realize the proximity that we already have with the people whom we study.

CCB: I recently heard historian Catherine Allgor say something quite similar about her study of women in an appearance on Mount Vernon’s Leadership and Legacy podcast with Lindsay Chervinsky, that while studying women, Allgor says that “women in history are actually quite similar to people.” Assuming a starting point of difference or distance is certainly helpful in some regards when looking into the past but remaining grounded in the shared human experience should pull the past, and its events and people, much closer to us.

Similarly, just as people in the past were people just like us, we have their lessons and tools to draw upon. As you just asked about the founding of the United States, the founding principles and civic virtues of the Revolutionary and Early Republic eras can and should continue to guide us through tough moments. The ability to compromise, to reach agreements in principle even if not in method, and to keep the uniting and dignified nature of humanity in mind should not be cast aside as old fashioned.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).