An interview with Christina Bambrick

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Fellow Dr. Christina R. Bambrick to discuss her new book, Constitutionalizing the Private Sphere: A Comparative Inquiry (2025). Dr. Bambrick is assistant professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame.

ED: What inspired you to become a political scientist?

CB: I first became interested in politics in high school. Growing up in a time of heightened partisan polarization led me to wonder how people with different backgrounds and commitments could come together to form a single polity. I did not have the terms yet, but I was basically interested in how liberal regimes deal with pluralism. I also had a wonderful U.S. Government teacher in my senior year who further piqued my interest in these kinds of questions and introduced me to such canonical texts as Aristotle’s Ethics and The Federalist Papers.

I went on to Scripps College for my undergraduate education, where I took wonderful classes in philosophy and politics. I also enrolled in classes at Claremont McKenna College, where I took seminars with JMC Scholar George Thomas on American and comparative constitutionalism. These classes were formative for me and put me on the path to graduate school. I applied to various programs, but given my interests in public law and political theory, the University of Texas was a perfect fit. With Gary Jacobsohn as my supervisor and other terrific professors like Jeff Tulis, I really could not have asked for a better graduate education.

ED: What led you to write your book, Constitutionalizing the Private Sphere: A Comparative Inquiry?

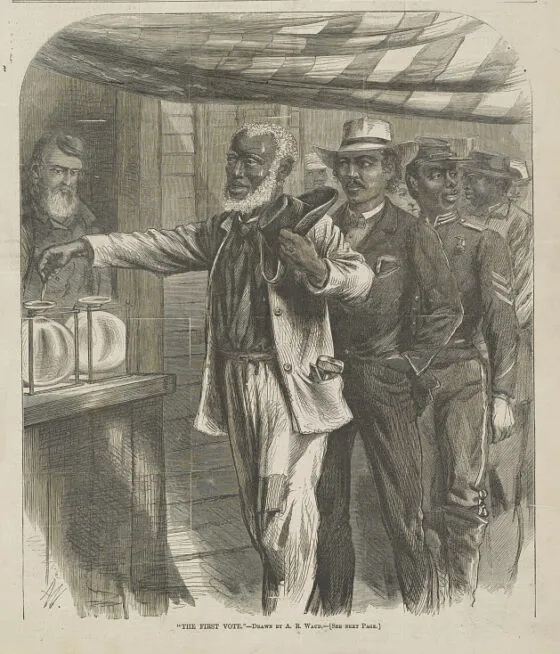

CB: The book began as my doctoral dissertation. I remember coming to my topic while studying for the comprehensive exam in public law. I was reading the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that introduced the “state action doctrine” in U.S. constitutional law. This is the doctrine that only state actors, i.e., not private actors, have constitutional duties to uphold rights. In that particular moment of U.S. history, the Supreme Court decided that the language of the Fourteenth Amendment obligated only state actors to the Constitution’s new commitment to “equal protection.” So, it compelled state governments, but not establishments like inns, theaters, and other privately-owned places.

Constitutional principles

CB: I found this legal doctrine and the questions it raised intriguing. On the one hand, I could see the value of regulating state actors and private actors according to different standards. More specifically, in the interest of preserving some space for pluralism, I could see value in not requiring private actors to subscribe to all public projects undertaken by the state. But on the other hand, this particular constitutional principle of equal protection and racial equality, seemed so fundamental.

Of course, the United States would ultimately address these social ills through the Civil Rights Act of 1964. But one had to wonder if a different outcome to the Civil Rights Cases, one that did allow us to think about private actors’ duties in constitutional terms, might have staved off some of the discrimination that would ensue in private spaces through the twentieth century.

As I would learn, constitutional actors in other countries do choose to address discrimination and a host of other issues in the private sphere, through the constitution itself. So, the book was borne of a kind of ambivalence and curiosity about other countries’ experiences in governing private spaces and non-state actors.

CB: As explained above in the U.S. context, traditional understandings hold that constitutions create obligations only for state actors. So, the state has duties to uphold a right to freedom of speech, or in other countries, perhaps a right to education or healthcare. This conception of a constitution, which obliges state actors, results in a separate private sphere that is not necessarily accountable for constitutional commitments, or at least not in the same way. In recent decades, however, courts and even constitution-makers have increasingly expanded the domain of constitutions so that they do speak to private actors and in private spaces. This model does not necessarily collapse the concepts of public and private, but also does not aspire to the same level of separation between these spheres. Instead, the norms that govern the state ultimately govern private actors as well. One might say the result is to “constitutionalize” the private sphere. The title is perhaps a bit provocative, but my hope was that it would invite people to ponder this increasingly common understanding of constitutionalism.

ED: What is horizontality, and what does this concept tell us about the republican tradition?

CB: Horizontality, horizontal effect, and horizontal application all refer to the idea that constitutional rights can create duties for private or non-state actors. One version of this practice allows the constitution to apply directly to private actors. In other words, the constitution is the proximate source of private actors’ duties. This is known as direct horizontal application. Probably more common are different versions of indirect horizontal application. These include courts deciding to interpret laws that govern private actors so that they align with constitutional principles, or alternatively, legislatures passing laws to govern private actors in line with constitutional principles.

The contribution of my book is to examine horizontality in its various forms through the lens of republican political theory. Of course, by “republican” I am not referring to the American political party, but rather the long tradition of political thought that dates back to such thinkers as Aristotle and Cicero (pictured), up to contemporary theories of neo-republicanism. In the book, I describe horizontality as a “republican vein in liberal constitutionalism” because I think this tradition sheds light on the ways that horizontality reshapes understandings of constitutionalism. In particular, horizontality orients the polity as a whole toward a kind of common good, a res publica or “public thing.” Furthermore, it puts a new emphasis on citizens’ duties, thus modifying conventional understandings of constitutionalism as a rights-centric enterprise. Thinking in terms of republicanism, I argue, illuminates both the continuities and innovations that horizontality brings to constitutional governance.

ED: Please share your favorite court case that you uncovered while researching this book and show us how it supports your overall argument.

CB: This is a tough question. I could probably pick a favorite case for each of the five contexts the book covers. One that stands out in my mind and that many people find interesting is the German Stadium Ban case from 2018. In this case, a 16-year-old fan of German football was permanently banned from a stadium for disorderly behavior.The individual filed a constitutional complaint that his rights had been violated, citing the costs of his exclusion from such a socially significant element of German culture as football. The Federal Constitutional Court (pictured below) agreed with this framing, specifying that his right to equal treatment under Article 3(1) was implicated. Previously, the Court had been hesitant to consider that private actors could be accountable for equality rights due to the potential incursions on individual liberty that might result.

Ultimately, the Court decided in favor of the football club, insofar as its unequal treatment of the disruptive fan was a legitimate exercise of the football club’s own right to private property. This more conservative outcome notwithstanding, the case serves to illustrate how horizontality operates in practice. It shows the balancing exercises that courts undertake to weigh the rights and duties of private actors involved in a dispute. Moreover, it highlights the way courts often proceed incrementally, not necessarily applying horizontality to all rights out the gate. Indeed, a court may be more inclined to employ horizontality in matters of greater historical or cultural significance. In this case, the fact that football looms large in German society figured into the Court’s reasoning. This, I think, corroborates my own republican reading of horizontal application.

While one might joke about the fact that this case was about football, I think it ultimately illustrates a republican instinct that private actors may have duties to further those commitments or values deemed important to public life and the common good.

ED: Explain how the US federal structure has “permitted some of the great evils of American history” while at the same time permitted “broader rights protections” (96).

CB: Whenever I teach constitutional law, one of my main objectives is to show my students how the American constitutional story has been shaped by federalism, the fact that the country is comprised of states with their own institutions and laws. How to understand and distinguish the powers of the national government versus those of the states has been a source of great debate throughout the country’s history, something on clear display in numerous landmark Supreme Court cases.

One can consider the constitutional arguments as well as more practical arguments for either side of the question. A proponent of strong federalism might argue that different states face distinctive issues and, to this extent, should have wide latitude to govern according to diverse needs and preferences. State constitutions often include socioeconomic rights or other unique features that we would never expect to find in the U.S. Constitution. The Illinois constitution includes coal miners’ rights, for example. On the other hand, the persistence of slavery well into the nineteenth century and, later, segregation into the twentieth century are paradigmatic examples of how the federal system allowed individual states to propagate such malicious practices. So, the history of U.S. federalism is a mixed one. The federal structure opens up additional political fora that may be used for good or for ill. More to the point, the federal structure means that horizontal application could possibly develop in the constitutional law of individual states, despite the fact that the state action doctrine precludes this practice at the national level.

ED: What does your book reveal about the American political tradition?

CB: My book demonstrates that the American conceptualization of nonstate action and private actors amounts to a constitutional choice. Even in the postbellum years, the state action doctrine was not necessarily predetermined. Rather, in the 1860s and 1870s, the Radical Republicans legislated according to a different understanding that sought to bring equality into private spaces.

The book’s comparative methodology also serves to show how the American approach to these issues is one among various others. One of the things I appreciate about comparative work in general is how it allows one to grasp a fuller range of political and constitutional possibilities. This is not necessarily to argue that constitutional actors in the United States should change the way we govern private actors. However, I do think a comparative perspective invites us to consider and justify the polity’s constitutional choices on this or any issue. We might ask, for example, if governing private action through statutory law, whether at the national or the state level, is appropriate when it bears on the polity’s most vital commitments. I think there is value in simply contemplating this. Indeed, my hope is that the book provides a framework to help people think more clearly about these enduring questions.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).