An interview with John C. Pinheiro

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC network member Dr. John C. Pinheiro to discuss his work on George Washington, John Dickinson, and the Founding Era. Dr. Pinheiro is the Director of Research at the Acton Institute.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

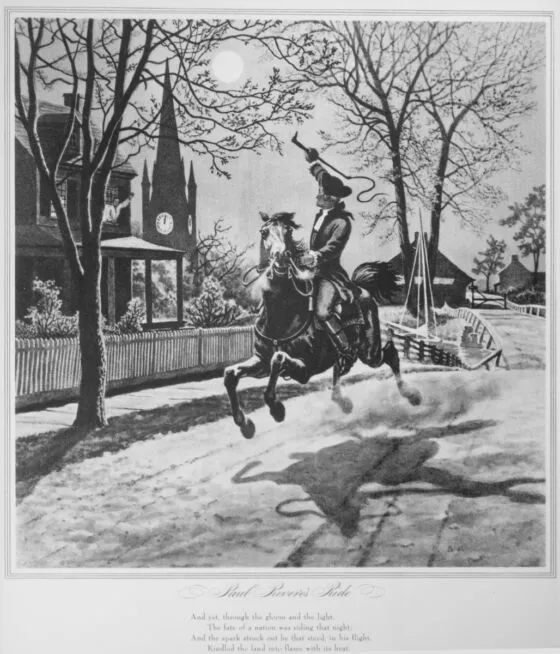

JCP: One of my oldest memories is my mother reading Longfellow’s “Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” to me. Around the same time I used to play my parents’ Johnny Horton records over and over again. Horton wrote and sang songs about Andrew Jackson, John Paul Jones, World War II, American explorers, the Civil War, among other topics. American history to Horton was a history of persons and places, not just ideas, and certainly not mere politics. But it was Longfellow’s poetry that first inspired me to want to know more about the American past, which also is my past.

My dad’s parents used to talk about the “old country” of Portugal as well. One grandfather told personal stories of World War I and the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake, one grandmother told me why she hated FDR and the other thought FDR did okay. The latter even claimed to have met John Dillinger when he was on the run. Everything was steeped in history, with history consisting mostly of stories–even tales of my dad’s experiences as a long distance runner in the 1950s and other very local stories. We often forget locality and place when we think of American history but the more we think just in terms of a national story or America as an idea, the more we lose sight of the fact that American history includes every American and every place in the United States. We learn our own past when we study history, and I was always drawn to wanting to know the truth of things.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

JCP: My first area of specialty is the early American republic, more specifically what is still known to many as the Age of Jackson–the time period of the 1820s-1840s when the United States was becoming more of a democracy, reformers (especially evangelical Protestants) were beginning to pose moral arguments against slavery, and massive immigration by German and Irish Catholics renewed a latent anti-Catholicism in the United States. Many Americans doubted that Catholics could be good citizens of any republic.

My first two books were about the consequential Mexican-American War of 1846-48. One of these, Manifest Ambition, looked at civil-military relations during the war. The other, the award-winning Missionaries of Republicanism, was a religious history of the war that focused on the role of a distinct brand of anti-Catholicism in American identity and Manifest Destiny sentiment. What sparked my interest in the Mexican-American War is that I’m a California native and I simply wanted to know more about the history of my home state. But more generally, I wanted to know more about the intense religiosity and culturally creative dynamism of this period that sits between the Founding and the Civil War.

ED: What is your area of specialty, and what sparked your interest in that topic?

JCP: My first area of specialty is the early American republic, more specifically what is still known to many as the Age of Jackson–the time period of the 1820s-1840s when the United States was becoming more of a democracy, reformers (especially evangelical Protestants) were beginning to pose moral arguments against slavery, and massive immigration by German and Irish Catholics renewed a latent anti-Catholicism in the United States. Many Americans doubted that Catholics could be good citizens of any republic.

My first two books were about the consequential Mexican-American War of 1846-48. One of these, Manifest Ambition, looked at civil-military relations during the war. The other, the award-winning Missionaries of Republicanism, was a religious history of the war that focused on the role of a distinct brand of anti-Catholicism in American identity and Manifest Destiny sentiment. What sparked my interest in the Mexican-American War is that I’m a California native and I simply wanted to know more about the history of my home state. But more generally, I wanted to know more about the intense religiosity and culturally creative dynamism of this period that sits between the Founding and the Civil War.

As long as I can remember

My second area of specialty is the American Founding. I have had an interest in the Revolutionary War and the Constitutional period as long as I can remember. But I especially began to deepen it during my time as assistant editor of the Papers of George Washington at the University of Virginia, which was my first job after earning my PhD in 2001. I have since spoke quite often on the American founding fathers, George Washington, and the whole period of the long American Revolution. I also wrote a book for Acton Institute that looks at the principles of the American Founding and assesses them in light of Catholic Social Teaching, called The American Experiment in Ordered Liberty.

ED: You recently published an essay titled “George Washington, Prudent Revolutionary.” What inspired this title, and what lessons in prudence can we draw from Washington’s life and leadership?

JCP: That essay grew out of a talk I gave at a recent meeting of the Philadelphia Society. I am speaking primarily to scholars on the Right who emulate Leftist historians by rejecting the American Founding as the best source for America’s core principles on liberty and order. Post-Liberal conservatives, for example, argue that the Founders attempted to build a new political system based on a radically individualist ideology closely related to the Enlightenment principles of the French Revolution. They say this means that the American Revolution was a fatally flawed ideological project. In response, they promote a muscular and interventionist U.S. government to reach what they claim are conservative ends.

Critics on the Left and Right might see different errors in the American Founding but they each propose an illiberal solution that involves using the managerial state to promote what they value and to punish what they reject. Along the way, they toss aside core commitments to limited government and religious, political, and economic liberty. This is a historical battle. Each knows that to achieve their statist goals they must undermine the Founding, either by pushing it back a century and half, like the 1619 Project, or by diminishing its accomplishment in ordered liberty as hopelessly rotten even in 1776 and 1787. I think if we can understand George Washington’s role in the long American Revolution, then we can go a long way toward inoculating us against such anti-Founding sentiment. We need to see the American Founding with fresh eyes. Then we can realize what we ought to preserve from our Revolutionary past as well as the best means for preserving it. If American conservatives are not to “conserve” the best of the Founding, then the term, “conservative,” becomes meaningless. One cannot find a more prudent and temperate revolutionary, or a less ideological leader devoted to limited, constitutional government, than George Washington.

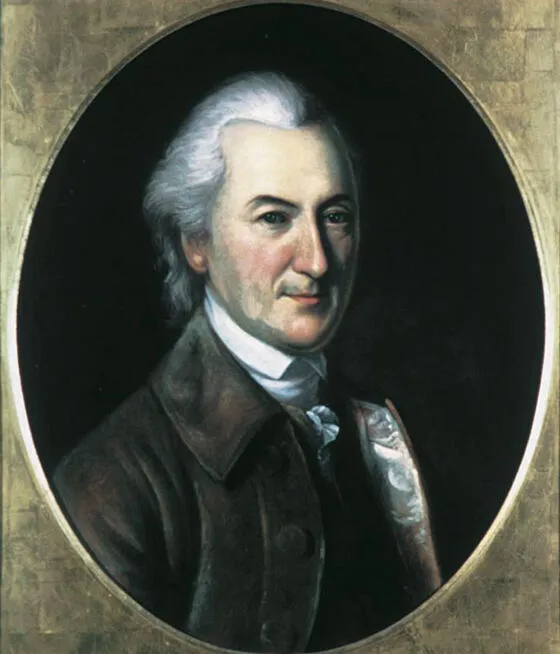

ED: Although John Dickinson may not have the same star-power as other Founders, his influence was substantial. How did Dickinson’s political actions and philosophy shape the American Founding, and what can we learn from his example today?

JCP: Dickinson possessed a strong religious and anthropological grounding, a historically informed sense of place, and a deep understanding of liberty’s relationship to property. Above all, he exhibited the virtues of prudence and temperance when answering the great question of how best to preserve Americans’ long-practiced liberties. Conversely, he downplayed theory and populism as reliable sources for good government.

John Dickinson’s prudence

For example, Dickinson called the 1765 Stamp Act unwise and illiberal. One’s property could never be secure under a system where there was taxation without representation. Dickinson recognized that private property is part of the foundation required for the freedom necessary for human flourishing. Men could not be happy without freedom, he said, and they could not be free if they could be taxed without their consent. That one’s property could not be requisitioned or taken or taxed without consent through some form of representation had deep roots in Christian history and the Hebrew Scriptures. It also was foundational to English liberty. When opposing the Townshend Duties as a violation of common law a couple of years later, Dickinson saw the latest taxes not as a good excuse to hold a rebellion, but rather as a misguided violation of constitutional tradition. The American response, he thought, should be a balance of loyalty to the Crown combined with an historical and common law argument. In other words, he applied prudence and temperance to defend Americans and preserve English traditions. He went out of his way to highlight the long tradition by which Americans and English had benefited.

ED: To what extent were Dickinson’s values shaped by Enlightenment thought? How did these ideas manifest in his writings and public service?

JCP: Dickinson is famous for saying at the Constitutional Convention, that “experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us.” This was a warning against ideology and a nod to the importance of prudence and moderation in solving real-world problems. That is, not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good, but also relying on what one knows best from the past, as opposed to one’s theories about the way things ought to be.

But I think there’s another quotation from Dickinson that speaks more directly to your question about the influence of Enlightenment ideas on him: “Our liberties do not come from charters; for these are only the declarations of preexisting rights. They do not depend on parchment or seals; but come from the King of Kings and the Lord of all the Earth.” True, there were many Enlightenments, and the Scottish Enlightenment was different in character than, say, the French Enlightenment. But Dickinson knew that concepts like consent and representation and other liberties were not the brainchild of seventeenth and eighteenth-century thinkers. Quaker influence in Pennsylvania told him this, as did his understanding of natural law.

When Dickinson talked about “no taxation without representation,” he was drawing on an idea of consent that already had deep roots in the Western heritage. In short, Dickinson’s understanding of human freedom was not the radical, atheistic version of liberalism we see in the French Revolution.

ED: Dickinson famously refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. What motivated his decision, and what does it reveal about the political tensions of the Founding Era?

JCP: It’s a good question to ask: Why would Dickinson oppose independence, when independence seemed be the natural end point of all his efforts since leading opposition to the Stamp Act in 1765? And can we determine whether this resulted from cowardice, as John Adams thought it did, or from prudence, the virtue statesmen need most? Jane Calvert argues that Quaker influence on Dickinson is especially key to understanding his opposition to American independence in 1776. The Quaker preference for nonviolent resistance and aversion to violent protest and revolution, according to Calvert, combined in Dickinson with Quaker constitutionalism. This is essentially correct.

I would add, though, that we ought to recall that non-Quaker George Washington also shared a similar opinion of the Boston Tea Party as deleterious to the preservation of Americans’ traditional liberties. Likewise, another non-Quaker, Thomas Jefferson, likewise preferred nonviolent resistance. To be clear, Dickinson was no pacifist, and he did lead men into combat during the Revolutionary War. But in 1776 he thought independence was premature. He worried Americans would be more likely to lose their liberties outside the British Empire than inside it. He thought the United States could not stay united for long outside the Empire, and they would end up making war on each other or be conquered one-by-one by other European powers. Dickinson was concerned with order. I think Dickinson’s religiously informed foundation, because it recognized the transcendent truth of human nature while prudently applying moral principles, law, and inherited wisdom to current questions, is a good shorthand definition of the best of the American conservative disposition.

Political tensions during the Founding Era included the fear of domination by Virginia and New York, how much authority any central government should have over the states that created it, and fear of imperial adversaries in North America who might divide and conquer the several states. We must remember that Americans fought most of the Revolutionary War as citizens of independent states, with a central government coming on board only in 1781. It was a valid question as to whether the wartime alliance among the states ought to continue after the war. Many thought that it should but there was much disagreement on what that government ought to look like. During my two decades as a history professor, I found that the most effective way to help students manage the complexity of the grand sweep of American history was to cast it as what Russell Kirk calls, in The Roots of American Order, “that healthful tension between order and freedom.” This tension involves balancing individual freedom with the common good, and this tension remains with us today. The American order requires a subsidiary role for a limited central government as well as a vibrant civil society.

ED: Washington held strong views on constitutionalism. How does his perspective continue to influence contemporary American civic life and constitutional understanding?

Washington was finely attuned to the separation of powers and the Constitution’s checks and balances. As president he carefully avoided overstepping what he saw as the boundaries of the Executive. He wielded the veto only twice, in both cases against bills he thought were unconstitutional. One of these had the support of Alexander Hamilton but he vetoed it anyway. He understood the role of precedent in Anglo-American constitutionalism and knew that everything he did would set a precedent, for good or ill.

JCP: He also knew that for a republic to be successful at self-rule, the population had to be virtuous. He believed religion was the source of morality, and therefore, of virtue. Everyone should read his Farewell Address on this point. As Russell Kirk put it, when “we lack order in the soul” we will lack “order in society.”

Washington was too vigorous an executive for some, but I would argue his understanding of the role of the American president was very restrained compared to what we later saw from Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln, not to mention most twentieth-century American presidents.

To answer your question, sad to say Washington’s views on constitutionalism have little influence in contemporary American civic life and constitutional understanding. This is as true on the Right today as it is on the Left. We see this in the jettisoning of constitutional scruples like, support for limited government under the rule of law, in favor of whatever gets promotes one’s own ideas or people and vanquishes one’s opponents.

This is why I think the work of the Jack Miller Center, and other organizations like the Federalist Society and Ciceronian Society, are so important. The importance of civics education cannot be understated, and there’s no way to engage in that education properly and wholly without recourse to American history and, in particular, without a look at how particular persons at particular times avoided ideological utopianism and instead employed virtues like temperance and prudence to balance the right to liberty with the need for order. American history is about persons and places, not simply ideas.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

JCP: I’ve learned, and Russell Kirk wrote about this so well, that the American Founding has much deeper intellectual, legal, and moral roots than the Enlightenment, and that Americans at their best have focused on the prudential application of their experience over and above ideological commitments. This conservative disposition is true even of Jefferson, who was more shaped by the western intellectual and religious heritage than he cared to admit. Along with his experience as a planter aristocrat in agrarian Virginia, this heritage gave him an optimistic but not utopian anthropology that influenced his views on religious, economic, and political liberty. It is in his promotion of the subsidiary role of the U.S. government in American life, rooted in this anthropology, that Jefferson left his most profound mark on the American conservative disposition.

Revolutions in the body politic

JCP: This preference for experience and tradition over ideology and radical change is the main thing that separates the American and French Revolutions. As I said about Dickinson already, most of the founders were not part of a new, fundamentally secular liberalism. They were not–most of them at least–working from an ideology which they hoped to instantiate in the body politic. Rather, they each in their own way and to varying degrees endeavored through the prudent application of principles, their knowledge of history, and their own experience to find ways to ensure American liberty in a judicious balance with order. Theirs was no Jacobin quest to build an unrealizable utopia. And their efforts bear little resemblance to the kind of liberalism condemned by post-liberals. We ought not conflate particular liberal ideas we find among leading American founders with radical, atheistic versions of liberalism we see in the eighteenth century.

JCP: I’ve also learned not to blame the Constitution for American corruption and decline. True, anti-Federalists made many predictions that have come to pass, but as I said recently to an audience at the Acton Institute, 230 years is a pretty good run. Moreover, these problems, like corruption for instance, have more to do with human nature than they do with the Constitution.

The reality of sin and human dignity counsel us that the best safeguard against corruption is small government and a free society that ensures space for the cultivation of virtue. Any Leviathan government invites corruption, because of its centralized power and authority.

We need constantly to measure ideals against experience, remembering that good government is rare but possible, whereas perfect government is nonexistent because it is impossible. Doing so will enrich and develop our understanding of the importance of the American Founding.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).