An interview with Mike Gray

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Network Member Mike Gray to talk about “dark tourism” during the Civil War and the relationship between history and pop culture. Dr. Gray is Professor of History and the Public History Coordinator at East Stroudsburg University.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

MG: Growing up in New Jersey, my parents often took me to historic sites along the East Coast. The importance of history was instilled in me at an early age, and I especially appreciated historical spaces, especially battlefields. My passion for history truly developed while studying at the university where I now teach.

At East Stroudsburg University, I originally majored in environmental science, hoping to become a forest ranger. However, I struggled with numbers, which made translating them into science difficult. Now, I study dates for historical context but deliver our national narrative with my own interpretations for my students. I often tease my students that I am just a glorified storyteller, but together, we dig deeper into the importance of sources, perspectives, and who is telling the story and why.

Mentors and career goals

MG: My intellectual journey was shaped by amazing mentors, including Dr. Jim Henwood and Dr. John Muncie at ESU, and Dr. Frank Byrne and Dr. John Hubbell at Kent State University. Going through the rigors of a doctoral program with slim job prospects was extremely challenging, but I always put in the hard work necessary to succeed in a competitive marketplace. That meant staying open to learning new methodologies in scholarship, teaching, listening, and networking—and of course, a sprinkling of good luck—so that my career goal of becoming a professor would come true.

I had back up plans for sure, but never wanted to give up on my dream of being a professor, even when my first job was teaching high school social studies. That job at New Egypt High School in South Jersey had a profound impact on my career journey. It helped me cut my proverbial teeth as a teacher by engaging an audience that did not necessarily want to be engaged. Frankly, it was the best thing that could have happened to me. I was a finalist at several universities because I had a high school teaching certificate—neither my first book, nor my doctorate was enough to get my foot in the door—and I seemed to possess the right ingredients at the right time.

I was hired to teach US history lower- and upper-level courses, grad classes, and also help supervise the Social Studies Education majors. As my career evolved, I slowly dropped that role. The high school teaching background got me in and hired as an assistant professor, but I was ready to advance to new roles that I am also especially passionate about—namely public history (with my love of historical sites). I eventually became the public history coordinator and helped my undergrad and graduate students network for internships and employment opportunities.

ED: What is your area of specialty and what sparked your interest in that topic?

MG: I am a 19th century US historian whose main specialty is the Civil War, but my sub-fields are US Military History, Frontier History, Sports History, Environmental History, and Public History. While working on my undergrad Senior Seminar paper at ESU, I was always intrigued with the Civil War, but even moreso with how history touches into the nooks and crannies of nearby and far off places—and sometimes it might be “dark history.” I wrote about Andersonville Prison as an undergrad, and as my research continued for my master’s thesis at ESU, I stumbled upon nearby Elmira Prison in New York state—which had a close death rate to that of Andersonville, which was roughly 28%, compared to Elmira, at 24.4%.

Researching Elmira

MG: As my research continued, I came across a tragic train wreck that had taken place in the Poconos, near Shohola, Pennsylvania, where ESU is located. My master’s thesis was a comparative analysis of Andersonville and Elmira. Since little was written about Elmira Prison. As I advanced on to my doctorate, my advisor, Dr. Bryne, suggested that Elmira Prison, with an economic spin, would be a great dissertation topic. I was fortunate that I had Dr. Byrne and Dr. John Hubbell to mentor me in the dissertation process, and I was able to sign a book contract before I graduated with my PhD.

ED: Tell us a little bit about the Voices of the Civil War series.

MG: My advisor at Kent State University helped initiate the series in the 1990s and was the first editor with University of Tennessee Press. Peter S. Carmichael succeeded him as the next editor, and I took over the role when Peter left for the Directorship of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. I had worked with the University of Tennessee Press Director, Scot Danforth, for manuscript reviews, and he knew the work of Frank Bryne with me being his student. I think Scot wanted me to help carry the legacy of Frank and Pete.

Since 2012, my tenure with UT and the Voices series has been a great asset, allowing me to share with my students the importance of editing not only manuscripts, but also historical documentaries, podcasts, and similar projects, too.

I help in the acquisition process of prospective volumes for our series, choosing what matches our historiographical trends, picking and choosing if they meet the protocol for our series, and networking with authors. After the editing is done, then I take on the mission of writing a foreword, so our readership sees how our latest volume fits into the larger context of our other volumes—more than 50 at this point. Essentially, I am justifying why our press felt that the press was justified in publishing the work.

ED: Explain the term “dark tourism” and give us an example of how it worked during the Civil War.

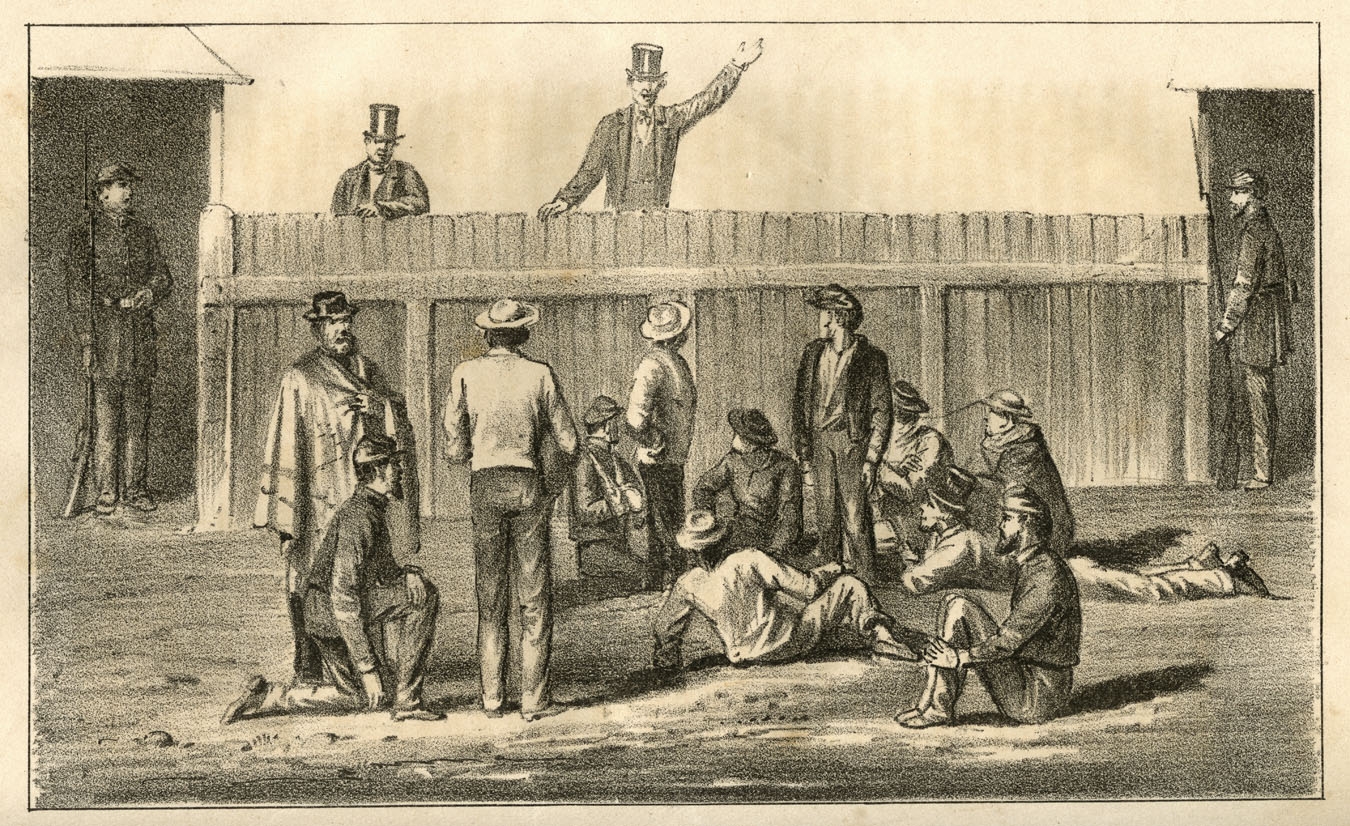

MG: Dark Tourism is a term that was coined in the mid 1990s by professors John Lennon and Malcom Foley, scholars who investigated how visitors might seek destinations with a macabre history. Students of the Civil War might be surprised that its prison camps became a central stop in the burgeoning field of “dark tourism.” Early dark tourists might frequent gladiator games in ancient Rome, attend public executions during the Middle Ages, or walk through the “bewildering halls” of misunderstood institutions such as the Bethlem Royal Hospital in London. Better known as the infamous Bedlam Asylum in the 1600s, it allowed for public viewing after payment was handed over.

In Antebellum America, similar “gawkers” frequented exhibits, fairs, travelling carnivals, asylums, museums, hospitals, and jails of a non-military structure. Grandstander Phineas T. Barnum established his own career in manipulating others in his American Museum, which he used under the guise of educating the public, charging them 25¢ per admission. His later circus and travelling menagerie established him as the so called “father” of the freak show—a popular nineteenth century form of entertainment in both England and the United States—as Barnum took full advantage of individuals with deformities, inconsistencies, or other physical anomalies that might challenge them.

Understanding “dark tourism”

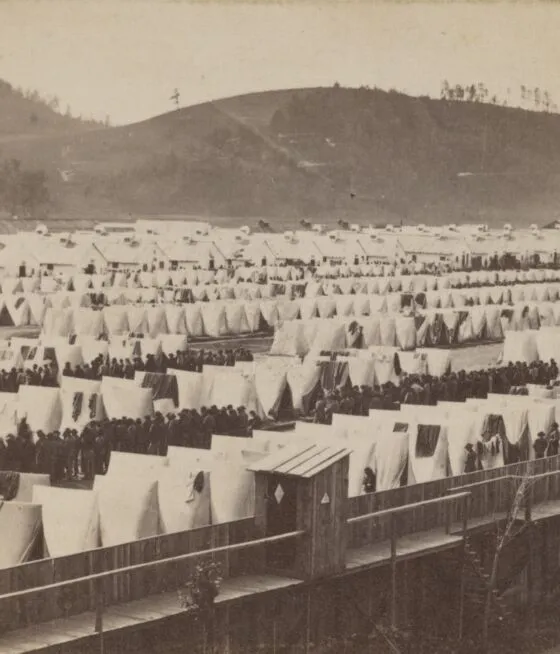

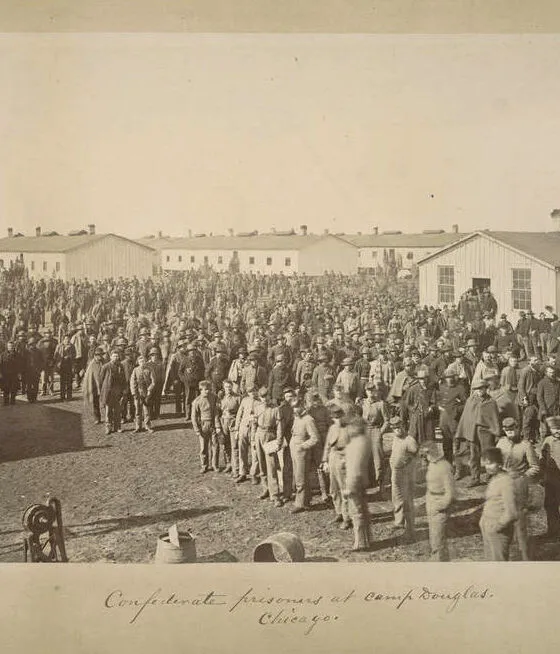

MG: I discovered a pattern in Civil War prison camps, which had an expansive number of “viewing episodes” that advanced capitalistic repetitions of competition, resulting in some prisons evolving into local tourist attractions—at the expense of prisoners and to the profit of businesspeople. Moreover, and contrary to many popular dark tourist stops in 19th century America, these Civil War prison locales, carefully overseen by the military, condoned the actions of civilians who participated in the war by “acting out” against prisoners through a variety of demonstrations. These “active” dark tourists left prisoners feeling exploited and dumfounded, and consequently, captives eventually communicated back at the civilian onlookers who goaded them on. Civil War prison viewing episodes for profit became primarily a Northern phenomenon, driven by Yankee entrepreneurship across a wide geographical span—from Camp Douglas in Chicago, through Johnson’s Island Prison in Ohio and further east to Elmira, New York, later in the war.

Also, the open-air nature of stockades borne from an impassioned civil war allowed for a new outlet where home front civilians, who might otherwise not be able to participate in the contest for reasons such as gender, race, age, disability, or other circumstances, could otherwise serve proactively.

Many non-combatants still yearned to be a tangible part of the conflict but if unable to serve in the field, they created their own “demonstrative battleground” at the walls of prisons, arming themselves with magnifying optics, hand gestures, and musical instruments rather than weapons; they voiced loud patriotic fervor in airing opinions into prison yards, rather than exhausting soldiering and physical contact from the front.

Although the South seemingly lagged behind the North in Civil War prison dark tourism, it too had its own viewing episodes—for example, the curious onlookers at Andersonville, an aspect noted on signage at the Andersonville National Historic Site. There are also accounts at some other Confederate confines, with many, but not all, near cities such as Richmond—Belle Isle had viewings episodes, for example, as did the highly attractive Libby Prison, like Johnson’s Island on the Northern home front. Southern civilians, just like their Northern counterparts, followed captives on their way to prison, but when doors were shut, so were many of the Confederate viewing opportunities.

The notion of “pay to view” was literally built north of the Mason-Dixon line. Even after the conflict, the Southern Libby Prison was removed brick by brick from Richmond and shipped north on 132 twenty-ton railroad cars to Chicago. Its 900,000 bricks were then reassembled into a museum at the Libby Prison War Museum in 1889, primarily for the 1893 World’s Fair, so individuals might tour its infamous halls after being charged admission. This manifested dark tourism of Civil War prisons into the post-war era. Ultimately, the façade would be used again for the old Chicago Colosseum, home to the Chicago Black Hawks from 1926-29

ED: You helped research the actress Jessica Biel’s ancestry for TLC’s show, Who Do You Think You Are? Describe that experience with us and how you conceive of the value of bringing together scholars and popular culture figures. What might surprise people about such collaborations?

MG: In 2015, my expertise on Civil War prisons resulted in an interview with CNN. That interview proved especially valuable in 2016, when national television’s The Learning Channel invited me to help uncover the story of Francis Brazier, the great-great-grandfather of Jessica Biel, for the popular show, Who Do You Think You Are.

A near escape

MG: Francis Brazier was incarcerated at the Alton Prison, an island prison on the Mississippi River near St. Louis. He attempted to escape with other prisoners, only to be shot in the back while trying to cross the river. Jess was great and so down to earth—she joined us and the crew for lunch during our trip—and talked about her upbringing and her interests with her husband, Justin Timberlake: golf and fly fishing, pastimes I do myself. This experience helped me with filming behind a camera, as it was an organic dialogue.

However, when I hosted Battlefield 101 on Military.com, which ran 14 short episodes dealing with an array of topics in warfare, I had to read off a teleprompter and stand still in one spot in front of a green screen, and it was much more nerve-wracking in the early episodes. It was a tougher methodology for me, since I enjoy moving around while I teach and not being anchored to a lectern. But just like teaching, you become more comfortable in that stationary environment, and I think I improved as the series continued.

Hosting Battlefield 101 helped me in 2024, when I appeared on national television again, this time with the History Channel’s “Prison Chronicles: Andersonville,” where I spoke to that Civil War prison’s high death rate. This was a sit-down session, where I was asked to answer questions in a conversational manner. I try bringing these experiences back to my students, particularly as my role as the Public History Coordinator at ESU. In these classes, we talk about how “history meets Hollywood” on a variety of levels, but especially all the behind-the-scenes work.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

MG: The human experience for sure, especially in working on Civil War prisons—and overcoming class conflict, even in Civil War prisons.

Overcoming adversity and embracing liberty and natural rights in captivity is a good lesson for all of us to learn.

There was an inmate social order that developed, as well as class distinctions among captured soldiers within many Civil War stockades. Camps for enlisted men, such as at Elmira, New York, saw a distinct social order evolve inside the camp; after adjusting to captivity, one might rise with education, ingenuity, and labor. Station in life prior to incarceration, on the outside, disintegrated as a struggle for survival manifested on the inside. Harsh imprisonment might break down military grade and social standing—no matter sergeant or private—and personal resilience and reaction to their circumstances formed the foundation of how they would live.

Those who could write might be hired as secretaries to prison officials and creative inmates could partake in service-oriented jobs at the marketplace, while healthier and harder working men labored on buildings. As one might ascend into these categories, others might fall; at the bottom of Elmira’s social order were vagrants who might be found scouring dump carts for food, too sick perhaps physically or emotionally, to fend off inevitable death. They gave employment to the grave diggers who shoveled for their own survival in a prison that had one of the highest death rates of any Northern prison (nearly one-quarter).

Conversely, it was no mistake that the officer prison at Johnson’s Island had one of the lowest death rates of all Civil War confines with less than 2%. Rank and status permeated throughout its stockade, from its keepers to its captives. A prisoner from the enlisted men’s Camp Chase simplified such an assertion, writing that “the prisoners on Johnson’s Island lived better.” Prisoner W.A. Wash concurred, “I am glad to say that prison life—in so well selected, arranged, and conducted a place as this—has been more agreeable than I anticipated.” But as Wash acclimated himself to his new surroundings, trying to “learn the ropes of the institution,” he noticed a definite distinction among the inmate population.

ED: What’s one thing you wish everyone knew about American history?

MG: How the human experience shapes our personal histories and helps us overcome adversity in our own lives. For example, we see the ingenuity of captives who found ways to survive or escape, and in the diversity of experiences while in captivity. Not all prisons were equally harsh—death rates varied—and important differences existed between the camps for officers and those for enlisted men.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Dr. Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).