An interview with Phillip Hamilton

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Network Member Phillip Hamilton to discuss his research on Henry and Lucy Knox.

Dr. Hamilton is a professor of history at Christopher Newport University.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

PH: It really began when I was a young boy growing up just outside of New York City. My father worked in the theater, but he also loved history and the French and Indian war, in particular. Therefore, we would periodically go on family weekend trips, and explore the Hudson Valley’s various eighteenth-century historical sites, including some critical Revolutionary War locations.

My parents also owned the old American Heritage illustrated histories, including The American Revolution and The Civil War. I can still remember pouring over the paintings, maps, and photographs in those volumes. Eventually, I began to read the texts of those books, and I became equally enthralled with the stories they were telling.

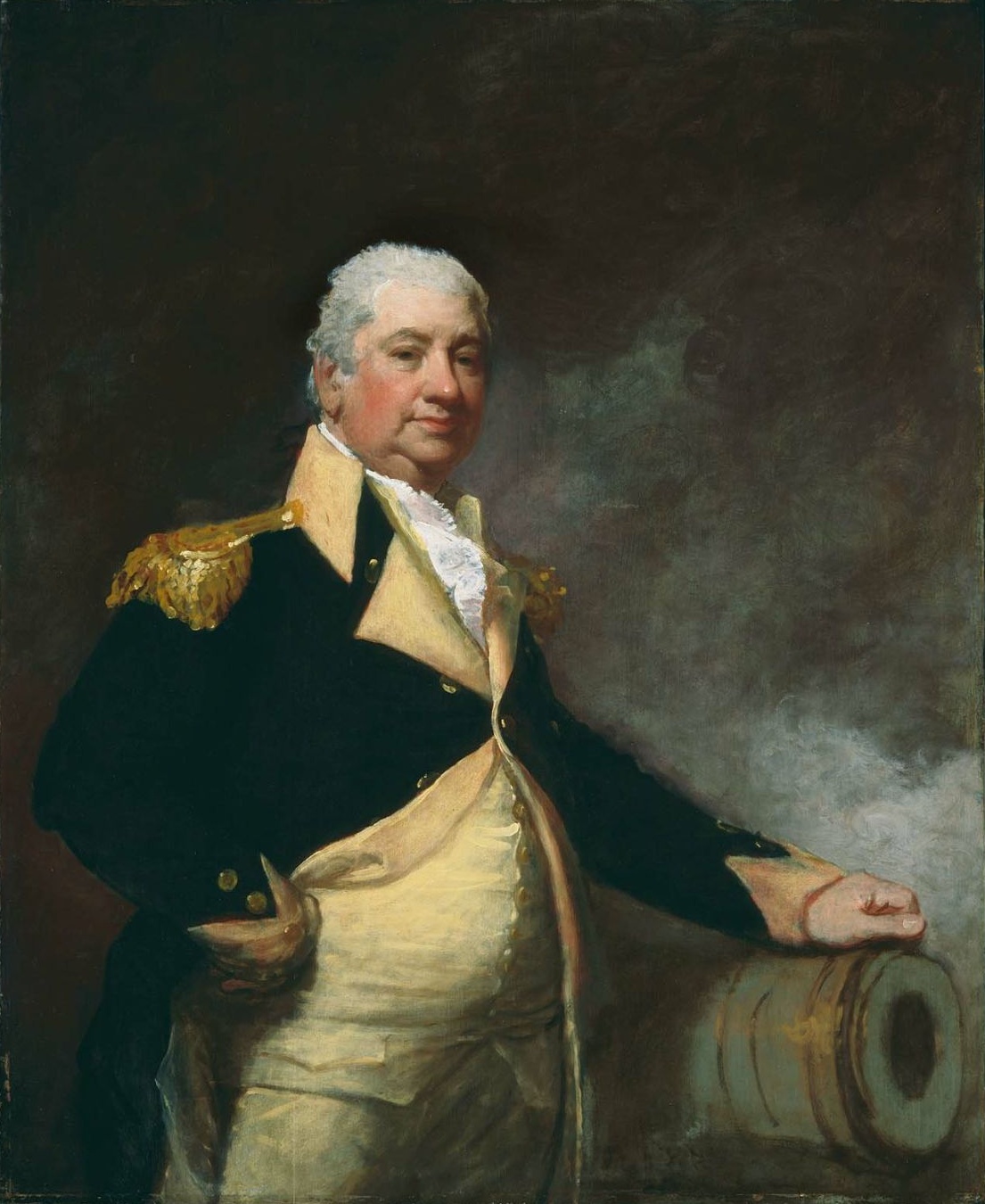

ED: Many Americans know Henry Knox because of Fort Knox and perhaps that he served as the first Secretary of War under George Washington. What are a few “must-know” features of Knox’s life that will help introduce him to those unfamiliar with his life and times?

PH: Yes, you’re correct that most people, if they heard of Knox at all, associate him with the fort bearing his name or they are vaguely aware that he was Washington’s first war secretary. But Knox was a remarkable figure in his own right, and he led a remarkable life. Prior to the American Revolution, he was born into a maritime family from Boston. But he possessed ambition and a love for the written word. Therefore, as a boy, he gained an apprenticeship in a local bookshop, where he impressed its owner with his diligence and capacity for hard work. In his spare time, Knox educated himself in the classics, history, literature, and, above all, in military science and artillery.

His ambition, moreover, never left him. And Knox spotted his main chance when he happened upon George Washington in July 1775, just two days after the General’s arrival in Cambridge. Indeed, even though Knox was committed to the cause of American liberty, he also saw the war as a means to advance himself. And here you can note the similarity between Knox and his colleague in the cabinet, Alexander Hamilton. Both men were ambitious and determined to rise within American society. Throughout the war, Knox not only rose to command the army’s artillery branch, but he served time-and-again as Washington’s “go-to” man.

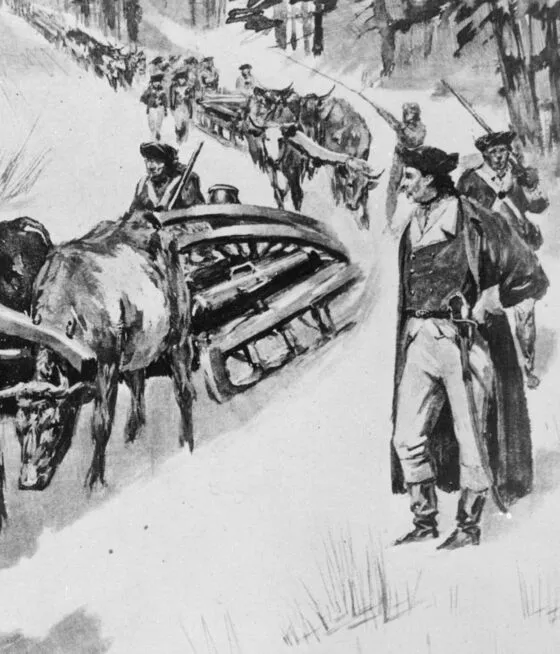

Breaking the siege

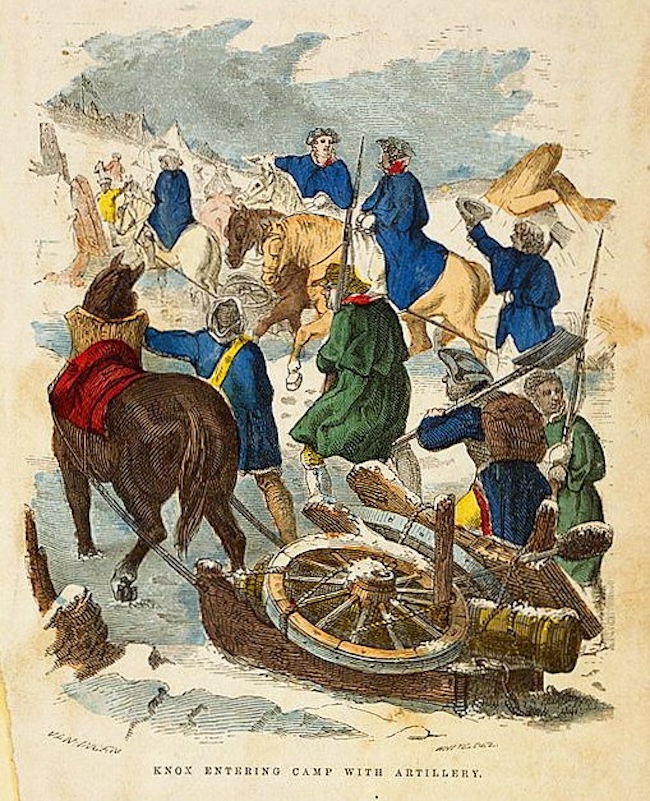

In fact, Knox repeatedly rescued the Continental Army at some of its most perilous moments. In the winter of 1775-76, he travelled to Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York to retrieve nearly sixty great guns, which he then transported across the Berkshires to artillery-starved American forces outside Boston.

A year later, after the Continental Army had suffered defeat after defeat in the New York campaign, Knox using his “stentorian lungs” directed 3000 men, eighteen cannon, and tons of ammunition across an ice-strewn Delaware River amid a terrible nor’easter, and, hence made possible the great victory at Trenton. In 1783, with the war all but won, Knox again worked closely with Washington to squelch the Newburgh conspiracy.

I believe, therefore, that Washington’s confidence in Knox and his ability to get things done led the new president to make him his first secretary of war.

ED: You note that Knox lived in two different worlds: the colonial world and the post-war American world. How successful was Knox able to navigate deference culture and the new democratic order?

PH: Well, all of us as human beings are born into one world and, if we live a full life, we will pass away from a very different one—different in terms of its culture, values, geopolitical situations, and technology. That’s true today and it was true in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Henry Knox was born in 1750 into a British American world that respected rank, hierarchy, and deference towards one’s betters; yet it was also a world that valued talent and ability. As a boy and later, as a young man, Knox possessed both the natural intelligence to understand this as well as the ambition to succeed within it.

In other words, he possessed the right skill set at the right time to succeed: a determination to educate himself, an affable personality, and a knack for presenting himself to the larger world as a gentleman.

He also had an impressive talent for cultivating friendships with men of higher rank. These abilities—combined with his unmistakable skills—permitted him to work his way into Washington’s inner circle, to command the army’s artillery branch, and to end the war as a major general.

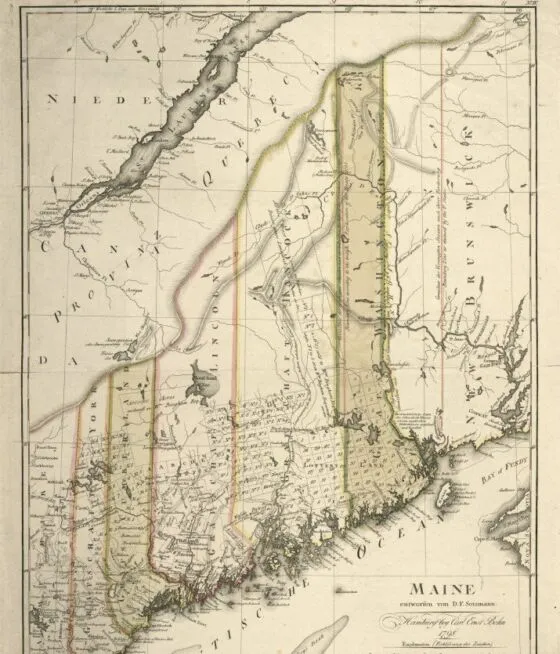

His Maine shortcoming

Although such traits allowed him to succeed during the war, they ironically left him unprepared for the democratic transformations unleashed by independence. As a result, Knox’s life began to unravel in the 1790s. Throughout the decade, for instance, he invested in massive land speculation schemes in Maine. Here he was following a path pursued by ambitious men of past generations (including George Washington). Indeed, he believed such activities would guarantee his financial security and validate his position as a “great man” within the new nation.

Again, like his one-time commander-in-chief, Knox also lived on a grand scale to further confirm his elevated status. These activities, however, ruined him. Amid the nation’s changing political attitudes and economic ways (which Knox neither fully recognized nor comprehended), his actions led to marginalization from public life, settler resistance upon his lands, and eventually to his own bankruptcy. Therefore, by the time of his death in 1806, Knox’s once-great reputation had collapsed, and he passed from the scene a relatively forgotten figure.

ED: You published a wonderful collection featuring the correspondence between Henry and his wife, Lucy Flucker. How did they meet? How does their correspondence differ from more well-known correspondents like John and Abigail Adams, and what does their correspondence tell us about the late colonial world?

PH: The couple met in Knox’s bookstore in 1772, when Henry was 22 and Lucy just 16. But it was love at first sight. Although Lucy’s father, Thomas Flucker, was the Royal Colonial Secretary and a staunch Loyalist, the couple married in 1774 on the eve of the Revolution. And when Knox fled Boston after Lexington and Concord in order to join the Continental Army, Lucy willingly followed him (even though that meant she would never see her family again).

Lucy and Henry

Because Knox was with the army during long stretches of the war, they wrote to each other whenever possible. And their letters are both informative and frequently quite moving. They are also very different from the John and Abigail letters. First of all, the Knoxes were much younger than the Adamses. When the war broke out, Lucy was still a teenager and Henry was just in his mid-20s. In other words, they were about the same age as most students in my classes. Their correspondence is different, moreover, in what they focus on. For example, Henry’s letters concentrate on military affairs, struggles within the army, and his relationships with his fellow officers. Therefore, one sees the war through a very different prism. Furthermore, as the war unfolds and becomes more transformative than anyone first imagined, you can see both partners maturing and, in the sense, growing up with each passing letter.

ED: Returning to Secretary of War Knox, who would you say were his greatest allies within the administration? Where did he position himself in relation to the famous political debates between Jefferson and Hamilton?

PH: Without a doubt, George Washington was his greatest ally and supporter within the administration. In fact, Washington would later write about Knox, “I can say with truth, there is no man in the United States with whom I have been in habits of greater intimacy;—no one whom I have loved more sincerely;—nor any for whom I have had a greater friendship.” Given their wartime experiences together, Washington came to have great respect for Knox’s military skills as well as his ability to get things done.

Their relationship sadly began to deteriorate when Knox focused on his land speculation schemes during the latter years of his secretaryship. I would also argue that he prioritized those plans over his official responsibilities, which was something the ever-dutiful Washington would not tolerate.

In terms of his politics, Henry Knox was a committed Federalist and frequently supported Hamilton in cabinet debates in matters dealing with foreign policy and national finance. But neither Hamilton nor Jefferson thought much of Knox’s political or intellectual acumen. For example, during the cabinet discussions about what to do about the troublesome French minister, Citizen Genet, Jefferson privately referred to Knox as “a fool,” both for taking Hamilton’s side in the debate and because of his, Knox’s, overall ignorance about the matter.

ED: How do you think Henry Knox would like to be remembered by Americans living today?

PH: I think he would, above all, want to be remembered for his military contributions during the American Revolution. Although he never independently commanded an army in the field (as did his more famous friend and colleague, Nathanael Greene), he nevertheless transformed the American artillery into the army’s most elite wing. He also introduced the latest tactical innovations in terms of deploying his men and guns in battle, and he also served as an inspirational officer to both his artillery officers and the enlisted men. But I additionally think he would want to be remembered for the many sacrifices he made for the cause.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

I have certainly come to respect the founding generation for having the courage to break free from Great Britain as well as for the many sacrifices they made for the cause of independence. -Phillip Hamilton

PH: I mentioned that Lucy Knox never saw any of her family members again after deciding to stay with her husband in the war’s early days. This was an incredibly difficult decision for this teenager, and she suffered mightily when her family broke off all contact with her. And that’s just one of the many sacrifices both men and women of this generation made.

Perhaps an even more important thing that I’ve learned about these people, is that they had the political wherewithal to establish a stable, functioning self-governing republic that has lasted now for centuries.

I realize that many of my colleagues in the academy these days like to criticize the founders for all of the things they did not do (the most obvious example is that they failed to get rid of slavery); but they did create a free society that, although admittedly far from perfect, permitted future generations to make changes to the republic as well as to improve and expand political participation and personal freedoms. These are all accomplishments that we ought to study and praise, not denigrate.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Dr. Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).