An interview with Tara Strauch

JMC Resident Historian Elliott Drago sat down with JMC Network Member Tara Strauch to discuss her research on religion, politics, holidays, and American Girl Dolls. Dr. Strauch is the Paul L. Cantrell Associate Professor of History at Centre College.

ED: What inspired you to become a historian?

TS: Juvenile historical fiction inspired me to become a historian. Series like American Girl, Dear America, and historical fiction by authors like Karen Hesse, Ann Rinaldi, and Elizabeth George Spears (among many others) brought history to life for me. These books also showed me that history was really storytelling. I also explored family history from an early age through 4-H. I completed a project called “Family History Treasure Hunt” and worked with my grandmothers to track down our ancestors. Going to local historical societies and learning the basics of archival research was so fun and exciting!

ED: You have an interesting pair of specialties—what are they, and why are you so interested in them?

TS: By training I’m a historian of the American Revolution and early republic. I specialize in religious history and am most interested in the intersection of religion and politics. My dissertation and earliest publications focused on how religious minority groups fit into the new nation—especially because many of these groups refused to take oaths and were skeptical of events like Thanksgiving and fast days.

I find 18th and 19th century American religious minorities very fascinating because they were navigating a narrow course; they had to prove that they were capable of upholding American political principles while also protecting their theological beliefs.

The tensions inherent in threading this needle led to religious schisms and many crises of conscience, but the hard work done by these small groups also led to greater clarity about what religious freedom meant which has continued to benefit Americans all the way to the present.

I have used my early specialization in religious and political identity to pivot into looking at the development of American culture—particularly the American holiday calendar and historically based popular culture like American Girl. I teach at a small liberal arts college where I have the flexibility to teach interesting classes.

If we took a holiday

TS: One of those classes is “A History of American Holidays,” where we explore our holiday calendar and how it came to be, what these holidays are, which have disappeared, and many other questions. This class came naturally out of my dissertation work on thanksgivings and fast days. Historians don’t spend enough time thinking about the history of ritual. We tend to leave that to sociologists, but we really can discover so much from considering our ritual past. My students in this class can think analytically about their own holiday calendars and make informed choices about how they spend their precious ritual time in the future. Hopefully, they also come away from the course with an understanding of how complex the relationship between individuals, politics, and culture can be. For example, Abraham Lincoln called for a national thanksgiving day during the Civil War, but he didn’t come up with the idea all on his own—he had been encouraged to do this by women across America who had been encouraged to write to their state and federal politicians by fashion magazine editor Sarah Josepha Hale.

The other class I created was “Playing with the Past” that uses the American Girl franchise to think about how we create historical narratives. (Ok, actually, this isn’t the only other class I have that does this. I also teach a class on AltHist which is a science fiction genre that considers alternate history. Like, what would happen if George Washington had been hung as a traitor!?)

My American Girl class gives my students the ability to write their own historical narratives. We read lots of juvenile historical fiction, we think about what playing with historical characters does for children’s intellectual development, and then we make our own characters.

We have had Triangle Shirtwaist Factory dolls, Filipino-American immigrant dolls, dolls that caught tuberculosis, worked in radium factories, and dolls that lived in gold-mining boom towns. The students do historical research, think about how to explain hard historical topics to children, and then create compelling characters. It is so much fun, but we also learn so much about the past and the present.

ED: From taking tea to walking a traditional hunting trail, innovation drives your classroom. What advice would you give to scholars hoping to incorporate similar experiences into their teaching? And do your students have a favorite historical tourism experience?

TS: I often tell people that “active learning” experiences do not have to be big, unwieldy projects that take undue time away from content-delivery. In my American Revolution course, I provide coffee and tea for students each class and invite them to switch drinks when they think that they would change their allegiance from Britain. This is active and engaging learning but it is also very internal—it doesn’t take time out of my class period most days.

In my 100-level survey course, I use one class period for a walk around town. I try to time this class during a busy time for students, and I invite them to leave their note-taking devices behind and to enjoy a historical walking tour. Students enjoy this class because it is physical and intellectual. We touch things and we move our bodies and I remind them that enjoying historical knowledge is important for living a rich and fulfilling life.

I’m actually a pretty traditional teacher when it comes to content delivery. I like short, interactive lectures and to scribble on a chalk board. But my lecture on the coming of the Civil War is so much more engaging when we are also pulling pieces out of a Jenga puzzle and waiting for it to fall over. What will tip the nation towards Civil War? Can the students think through cause and effect?

Quakers taking a stand

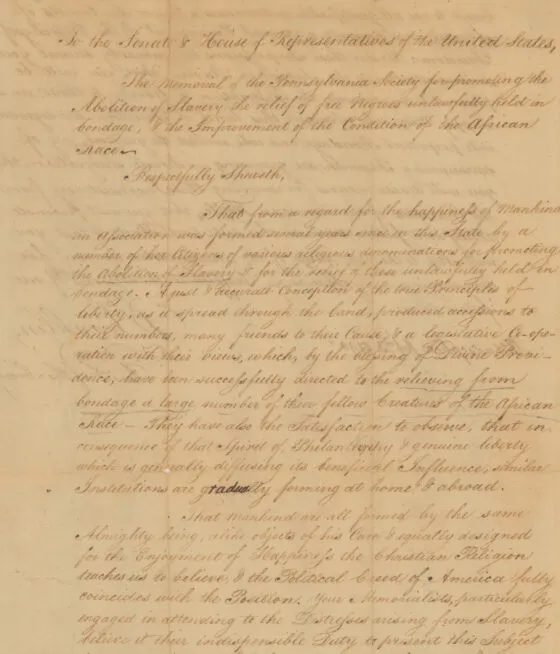

ED: Your focus on Quaker communities requires illuminating the relationship between religion and politics in the 18th century. Which primary source helps us best understand that world through Quaker eyes?

TS: If I have to choose just one 18th century primary source, I would probably choose the Petition from the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery to the First Congress in 1790. This document lays out the Quaker abolitionist argument but also shows that while religion and politics were separate categories in the 18th century, they were also mutually supportive. The petition says, “That mankind are all formed by the same Almighty being, alike objects of his Care & equally designed for the Enjoyment of Happiness the Christian Religion teaches us to believe & the Political Creed of America fully coincides with the Position.”

For Quakers, equality was very important and by 1790, many Quakers hoped and prayed that the American government would also come to believe in that same spiritual and physical equality. This document was signed by Benjamin Franklin, the president of the Society. Franklin was many, many things but definitely not a Quaker in good standing. Yet, Quakers were politically canny and saw the utility in having this well-known, persuasive, abolitionist leader as the leader of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery.

ED: Can you share what you value most about integrating popular culture topics into academic scholarship? Have you run across other popular culture artifacts that might push a student to study history? Conan O’Brien’s visiting the American Girl comes to mind.

American popular culture supposes that most Americans have a fairly wide base of knowledge about American history—The recent SNL sketches with Nate Bargatze as George Washington are a really good example. These pop culture uses of the past are very circular; you can’t understand why they are funny if you don’t understand American history. You also can’t understand how these sketches are challenging American ideas about the past and the present if you don’t understand the historical premises they are built on. Another classic example here are School House Rocks songs. Most of my students have seen “No More Kings” or “The Shot Heard Round the World” but have never thought of it as a historical narrative that is making an argument about the past.

Historians do themselves a disservice when we limit historical narratives to academic books, lectures, and journal articles. Americans are inventing their own historical narratives all the time through TV shows, movies, fiction, and SNL sketches. My students love to tell me about what they learned from Hamilton, but also from Liberty’s Kids, Gangs of New York, and even the Animaniacs. Our students must be able to analyze these narratives if they are going to be careful, thoughtful citizens. So, I love to use popular culture as a way of helping students translate the skills they are learning in the classroom to the wider world.

If academics can’t talk about Conan O’Brien at the American Girl stores, then I don’t want to be an academic! That whole bit is vintage Conan, a little awkward, a little sincere, and very funny—well, I find it funny, but my students mostly don’t. Why don’t my students find it funny? In part because they find jokes about gender norms less funny than I do. We can learn a lot from the humor disconnect here—Conan understands that the American Girl Stores are a female space that he was humorously invading. And American Girl stories were spaces that American girls (note the lack of capital letter here!) could inhabit. The historical stories were about girls like them. That creation of an imaginary historical space was needed because girls in the 1990s were being encouraged to think that everything in America could be for them—they could be the president, and they could imagine themselves in the past too! But, without any previous female American president to teach American girls about, Pleasant Rowland instead created a way for American girls to connect themselves to America’s past and present through pretend play and historical fiction.

An American Girl Anthology

ED: Tell us a little bit about your most recent project.

TS: I have an essay in a recently published edited collection, An American Girl Anthology, about the shared educational goals of American Girl and the National History Standards project in the 1990s. Both the company and the standards were pushing for more attention to social and cultural history. This new emphasis on underrepresented people, especially the daily life of children, created a generation of Americans interested in new questions about the past. I am excited to keep studying the “History Wars” in the 1990s and the rise of children’s cultural history and historical fiction because I don’t think the historical discipline has thought enough about where our academic interests and assumptions come from.

ED: What has your scholarship taught you about America’s founding principles and history?

TS: One of my takeaways from studying the Revolutionary era is that there were as many opinions and viewpoints on what America was and how it should be governed as there were people. One of the things that makes the creation of America exceptional is that so many individuals came to a consensus about how to make a republic.

Even when you look at people in the revolutionary generation who were removed from the political process, people like Mennonites and other German sectarians, they accepted the Articles of Confederation and eventually the Constitution as really good attempts at democratic governance. Was the Constitution perfect? No! But was it good enough? Definitely! In part, that certainty was possible because the Constitution created methods for expressing grievances and pursuing change. These minority groups liked that the Constitution was a living, breathing document.

There are very few topics where American leaders, let alone the American people, completely agreed on what the nation was, how it should be governed, and what should happen next. The agreement was instead about potential—America had the potential to be a good democracy. I always encourage my students to think about how important the future was to the Revolutionary generation. America’s history is not one of consensus, although consensus sometimes happens. America’s history is not about making a perfect foundational document either. America’s founding generation assumed that America could, someday, be a political and moral good in the world. I come back to that foundational optimism and hope for the future again and again.

ED: Thank you for your time!

Dr. Elliott Drago serves as the JMC’s Resident Manager of Network Engagement & Resident Historian. He is a historian of American history and the author of Street Diplomacy: The Politics of Slavery and Freedom in Philadelphia, 1820-1850 (Johns-Hopkins University Press, 2022).